Once upon a time, further back than I can put a real date on, recent enough that New York City’s Metropolitan Transit Authority had come up with a system of graffiti-free trains but distant enough that we’d yet to realize just how mutable this art form could be as it migrated off the trains onto the face of the city itself and transplanted itself around the world as a global movement, I remember doing a story on a bunch of kids, barely teens at the time, who were pioneering a then new medium called ‘scratchiti.’ In the amped up war on vandalism, the city had finally found a way to make the use of aerosol spray paint and ink-based markers practically obsolete on the subways, but youth had found another way to make its mark—crudely writing tags with grinders and even keys on the windows of the trains. A quarter century hence we might remember this time as the absolute aesthetic nadir of graffiti culture, for indeed this was about as artless as it could be, especially in the wake of graffiti’s golden age of vibrant and sophisticated full car pieces during the seventies and eighties, but as a signifier of ongoing social resistance and the urgency of self-expression, it felt monumental. The takeaway then, at least for this writer, was that whenever the MTA might come up with scratch-resistant windows there would simply be some other manifestation; that we were engaging in a no-win game of adaptability and escalation that might just as easily lead to people carving their names with jackhammers into the subway platforms.

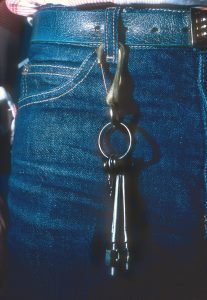

Thankfully, many municipalities have come to realize the hopelessness of any war on graffiti, and much as in that other specious overreach of law and order, the contemporaneous war on drugs, there has been some recognition of the inherent bias and folly of criminalizing our own kids with draconian punishments for victimless crimes. For whatever grim and slim lessons we have learned, and however we may have adapted somewhat saner rehabilitative or permissive strategies for dealing with these unruly energies and expressions, we still seemingly fail to fully recognize that what we see as an urge is in fact so primary as to be a need, or just as significantly, how that need engenders myriad new forms of ad hoc, impromptu, and adaptive methods in which most anything at hand can be turned into a tool of the trade. Much as we may limit the sales of certain materials to minors, or even make it illegal for them to possess things as basic as a simple Sharpie, we may be reminded, in light of the various repurposed graffiti implements on view here, of William Burroughs’s memorable quip that “nobody owns life but anyone who can pick up a frying pan owns death.” As long as we continue to make one of the oldest and most fundamental human impulses a crime, our restrictions on real or perceived acts of violence on public space perpetrated by alienated youth will only produce a broader and more inventive array of weapons.

Graffiti, as old as recorded history, and fundamental to written and visual language as the “other voice,” has long been a close companion to the most rebellious expressions of youth, from the Situationist graffiti of the 1968 student revolts to Punk’s DIY modes of branding and advertising to, most evidently, the foundational role of graffiti in the birth of Hip Hop. Born of alterity and perpetuated as an oppositional, anonymous, and outlaw vox populi raised in rejoinder against the hegemonic forces of status quo authority, the devices of graffiti have been as temporal as its terms, necessities mother of its inventions, ingenuities partner to its ambition. And when we consider how these implements form a kind of tactical arsenal of homemade modifications, there is in that glorious tradition of form following function a street level folk art at work here. Passed on generationally through a lineage of traditions both discrete and explicit and sustained by the ingenuity of adherents adapting to the vicissitudes of circumstance, the tools that graffiti artists (largely self-taught) devise themselves have a kind of folkloric quality. Somewhere within the vested interests of private property, the urban politics of destruction and the social taboos of deviance, we have criminalized the tools along with their use, but as purely formal and functional objects we may admire them as expressions of graffiti’s innovative esprit as well as its handmade naturalness.

PHOTOGRAPH.

If we ignore for a moment the purpose of these modified and manufactured devices, admire them for their form and inherent cleverness regardless of their intent, there’s something dearly genuine, unselfconscious, unaffected, and spontaneous about these makeshift ingenuities that invoke a fetish of urban folk. That is, beyond the relative sophistication at work here—evident, for example, in the technology of light graffiti, the chemistry of permanent inks, the forging of keys or the engineering involved in turning something like a fire extinguisher into a powerful spray can— these uncanny implements speak to an aura of authenticity that is ever more rare and seductive in the realm of slick fabrications and self-conscious intimations of post-modernism. It’s possible to be reminded here of a less well known incident from the notorious 1965 Newport Folk Festival in which Dylan shocked the traditionalists by going electric. While the howling sense of betrayal registered by the purists when Dylan shifted the poetics of old school Americana to the rowdy vernacular of Rock is well documented, an even more telling moment came when Albert Grossman (Dylan’s manager) got into a fistfight backstage with the great folklorist Alan Lomax. Even before the scandal of Dylan’s performance later that evening, his manager’s assault on Lomax, whose field recordings dating back to the thirties established a canon of American music from Woody Guthrie to Lead Belly and Muddy Waters, was sparked when Lomax reportedly introduced the Paul Butterfield Blues Band by saying, “there used to be a time when a farmer would take a box, glue an axe handle to it, put some strings on it, sit down in the shade of a tree and play some blues for himself and his friends.”

Lomax’s implication that all the “fancy hardware” was counter to the truth and primacy of the art form is relevant to our consideration of artists’ tools as arrayed along an axis of utility and integrity. Art-making itself, so often directed and defined by innovations and inventions yet constantly measured in turn by precepts of imagination and skill that instinctively distrust mechanical and technological facility, is varyingly assessed by these ambivalent, contradictory, and oddly relative standards. Within such a broad purview, the choice of tools can come to describe the work as mere craft or design, something utterly revolutionary and visionary, or just too easy in its reliance on external tricks. Against myriad biases—the primacy of the artist’s hand, the insistent supposition that “anyone could do this,” the modernist ratification of doing it first, or the rewarding of certain mediums as fine art to the diminishment of others as craft—we are constantly evaluating the techniques and materiality of art with conscious and unconscious attractions or disinclinations to the tools by which art is made. It’s really too complicated to examine here why a painter’s brush is held in higher esteem than a potter’s wheel, or to consider the various trials and tribulations by which some mediums like photography or digital art have struggled for validation, but with all this in mind there’s no ignoring a similar illogic of respect and refusal within street art regarding the various tools of the trade.

© MARTHA COOPER, 1980.

One last matter we need to address in considering utility is that all tools are not created equal. Just as usage defines the function of any tool, what we might call the mutability of Burroughs’s frying pan, so too does disuse characterize a kind of dysfunction. Any casual stroll through a musical instrument museum is rife with countless examples of obsolescence: instruments that by some flaw or impracticality in their design have failed to find composers to put them into the classical canon, musicians to take pleasure in their possibilities, or audiences to sustain their continued production and use. Whatever the instrument, we might say that once it stops being used it becomes an artifact. Indeed there are objects in this exhibition that exist as artifacts or may in time prove more historically interesting than useful. Graffiti is itself an art of the ephemeral, each mark destined to an erasure due to the forces of nature and man, diminished by the weather and constantly facing eradication by another artist’s hand or by the civic buff, so it is perhaps appropriate to already discern in the history of its evolution a rapid turnover of tools.

Fine art is full of experimental cul-de-sacs, novelties that did not quite pass the test of time, materials that have been abandoned for being too toxic or not archival enough, tools like the airbrush that brushed too close to kitsch, like reel to reel video or super 8 film or the copy machine (which for a time had entire departments dedicated to it in art schools) that get supplanted by newer more versatile technologies. Hip Hop, of which graffiti was a foundational pillar, is the ultimate DIY movement of repurposed tools, and much in the same way that mixing elements from old records between turntables could create a whole new sonic landscape, the adoption of lowly commercial spray paints by kids for completely different purposes helped propel that most primal instinct of mark-making (the urge to say “I was here”) into an art form. Each has spawned an entire cottage industry of tools, and to look at the earliest low quality spray paints to be adopted by this subculture in light of the high end manufacture of paints and markers made specifically for graffiti today is to witness relics of another time and utility. Which of these many implements we call tools of the trade will make it through the historical eye of the needle to become a fixture on the tool belt of artists generations from now is anyone’s guess. Only fools predict the future, but for those of us who can enjoy the folly of the moment, there is at this very moment a rapturous and dizzying field of possibility on display in the imagining of utility in contemporary graffiti art.

STEVE WEINIK, 2013.

PHOTOGRAPH.

Carlo McCormick is a critic and curator based in NYC. He is Senior Editor of PAPER magazine.