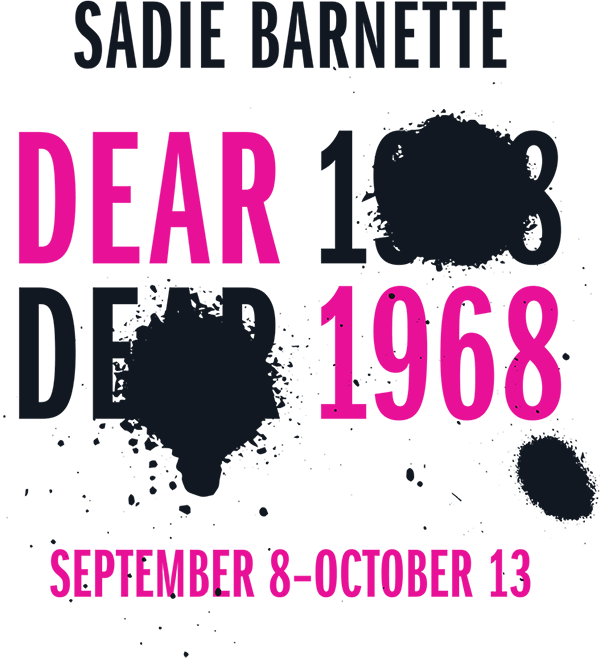

Interview with Sadie Barnette by Assistant Professor of Visual Studies Christina Knight

- With beautifully annotated parts of your father’s FBI file on display, Dear 1968,… reflects on the black radicalism of the late ’60s, but also on your particular relationship to your father. What was it like growing up with a parent who was in the Black Panther Party, and why have you chosen to center that story in the show?

While my dad was long out of the Panthers by the time I was born, both of my parents dedicated their professional lives to workers’ rights, and I grew up with a political awareness and a systemic analysis. The fact that my father was in the Black Panthers led me to view history not as the abstract distant past, but as family stories. We often separate the two, but as I’ve shared this project I’ve had many people tell me that their family members also played important roles in various movements and that they had always wanted to delve deeper into their stories. I encourage people to talk to their grandparents, record and tell these stories. History is not just in books and is not just about the names we remember, but also about the thousands of people who were there before it was history.

- Some of the work in the show engages explicitly with COINTELPRO, the FBI surveillance program run by J. Edgar Hoover that (often illegally) targeted political activists like your father. Amazingly, a former Haverford physics professor, Bill Davidon, played an important role in exposing the FBI’s surveillance activities by organizing a famous 1971 break-in at an FBI office in Media, PA. I think it is crucial to remember how many ordinary people put themselves at risk during that time. What can people today learn from those actions, especially given the ubiquity of contemporary surveillance technologies?

Yes, I have been reading about Davidon and his team in Betty Medsger’s amazing 2014 book, The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI, so when I was invited to show this work at Haverford College I was happy to have an opportunity to honor them in my work. There was no way for them to know the payoff of the great risks they took, but they acted anyway, and I don’t think it’s hyperbole to say they changed the world. For this exhibition, I created a drawing that imagined a logo for the name the eight “burglars” gave themselves—the Citizens Commission to Investigate the FBI. By giving themselves this official title, they imagined a world where the government is accountable to the people. They broke in because they rightly suspected that the FBI wasn’t simply gathering information, but was actively sabotaging their antiwar organizing. They weren’t fighting for privacy; they were fighting for the right to dissent.

- I like this clarification, though I think the rights to dissent and privacy have always been intimately related for black people. For instance in Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness, Simone Browne begins by discussing Frantz Fanon’s FBI file in order to suggest that surveillance (even going back to the optics of slave ships) has always shaped “the fact of blackness.” Does this idea resonate at all with your work?

Yes, exactly. There’s no privacy without freedom, and no freedom without dissent, and the black American experience has known neither privacy nor freedom. One of the findings of the Media burglars was documentation that the FBI was conducting surveillance on every black student at Swarthmore College.

- I was lucky enough to meet you on a sunny day in your beautiful studio in Oakland surrounded by woodshops (and chickens!) as well as new condos and construction projects. Can you talk about how a changing California, especially Oakland, shows up in your work?

The Black Panther Party was founded in Oakland, California. This city has always had a seemingly disproportionate amount of political and cultural genius. With the skyrocketing cost of housing in San Francisco, and everything being for sale to the highest bidder, Oakland’s demographic is changing a lot. When we think about what an impact the Black Panther Party had on society and the imagination of the people, we see why it’s so important to have cultural hubs and black cities, and I fear desperately for the future of political thought and culture if we don’t have those anymore. It’s not so much that I make work about Oakland as that Oakland is a part of my authorial perspective; Oakland isn’t the subject, it’s the language. This is most successful when a viewer versed in the vernacular recognizes Oakland’s presence/vibe in the work even when there’s nothing explicitly depicting Oakland (like street signs or BART stations).

- In engaging black lives and histories, the show feels political without being didactic. Can you talk about what kinds of conversations you would like the work to start among viewers, particularly during this especially polarizing political moment?

Thank you, that’s intentional and important to me. I don’t use art to do what I think political speech, non-fiction history, or documentary film can do better. I present black family, and the fact that some people and policies act like black lives don’t matter pushes up against that. Being black is inherently political because the world is still racist. By employing abstraction and distance, I am trying to complicate an either/or framework. I hope that my work allows viewers to hold opposites, reframe things, and imagine a radically different set of principles around which to organize a society, a type of third space of which I think the politics of the future must be born.

- I think part of what is so striking about Dear 1968,… is your ability to work across mediums with agility, meanwhile maintaining a coherent through-line. How do you go about selecting a medium when you approach a new body of work?

I start with the idea or the content. Because I work in so many mediums, I don’t have a ritualistic engagement with any one process. So when I enter the studio, the first thing I’m engaging with is the idea. It’s often challenging to know where to start, and I might scrap the first few attempts if the form seems arbitrary. But usually, after a good amount of anxiety, I recognize the medium that allows for the most symbiotic relationship between the content and the form—where each pushes the other forward. By using so many different mediums, I also acknowledge the failures of each of them, and still relish the attempts.

- A viewer can’t help but notice your attention to surfaces, particularly your use of neon colors, glitter, and sparkle. Why do these materials speak to you as an artist? How do you go about incorporating them into more minimalist or conceptual pieces?

Glitter is about seduction and joy, but also artifice. I often use glitter to talk about transcendence, ecstasy, and escape. I love when that works, but also when it fails, and you realize that it’s just a piece of paper. In the particular instance of this project about my father being under the surveillance of the FBI, I figured glitter and pink and rhinestone hearts would be the most antithetical to J. Edgar Hoover’s agenda.

- Your images feel really rooted in the here and now, but also in a kind of otherworldly space. Is your work in dialogue with Afro-futurism or other kinds of speculative genres?

Yes! I’ve been very informed and inspired by the Afro-futurist genre, even before I knew that term. The hip-hop duo OutKast (1996 ATLiens and 1998 Aquemini albums) was perhaps the first and deepest of those influences. I don’t think of my work as exactly inside of this tradition, but more as sampling, quoting, referencing, or bumping into it.

- I am so excited for students to see your show, particularly Visual Studies students who are eager to think about how images can either reproduce or challenge the status quo. What advice would you give those students on how to be critical consumers of images, whether they are approaching them as artists or as scholars?

That’s a good question. The drawing of my father’s mug shot in the exhibition does exactly that—it calls into question how images function, and what happens when someone is “mug-shot.” The reason I chose to render a drawing of the mug shot, as opposed to a more glorious photo of my dad, was to question the mechanics of criminalization and how instantly dehumanizing the mug shot device is. Every year on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, I like it when people post Dr. King’s mug shot, to show how he was considered an enemy by the state, as opposed to images of him used in advertising or on postage stamps that may have you believe the mainstream always honored his ideas.

Sadie Barnette is from Oakland, CA. She earned her BFA from CalArts and her MFA from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has been exhibited throughout the United States and internationally at venues including The Studio Museum in Harlem (where she was Artist in Residence), the California African American Museum, the Oakland Museum of California, the Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, The Mistake Room and Charlie James Gallery in Los Angeles, and Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg, South Africa. Barnette has been featured in The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The Guardian UK, Artforum, Vogue, and Forbes, among other publications. Her work is in the permanent collections of museums such as The Pérez Art Museum in Miami, the California African American Museum, and The Studio Museum in Harlem. Barnette lives and works in Oakland, CA and Compton, CA.

Christina Knight is Assistant Professor of Visual Studies at Haverford College as well as the Director of the Visual Studies Program. Before joining the Haverford faculty, she was a Consortium for Faculty Diversity Postdoctoral Fellow at Bowdoin College as well as a Ford Foundation Diversity Fellow. Knight’s work examines the connection between embodied practices and identity, the relationship between race and the visual field, and the queer imaginary. She is currently completing a book manuscript that focuses on representations of the Middle Passage in contemporary American visual art and performance. Additionally, Knight is working on a new project that examines the influences of drag culture on contemporary black art.