Marianne Nicolson

“Come ghosts, you whose night is day and whose day is night in this Great House, I beg you, Great Healer, to take pity on us and restore us to life.”

I was referring to a number of things in this text I wrote for The House of the Ghosts, including the belief we hold that the ghost world is the reverse of ours. We are mirrors of one another. The ghost world is not something separate or removed from us, but is a part of our everyday existence…

In referring to “this Great House,” I wanted to use the metaphor of the world. When we refer in an honorific way to the world as such, it means we all live here together. It is something that contains all of us. In the second part, “I beg you, Great Healer,” I use the name Hai’yałiligas, the literal translation of Great Healer, to refer to the ghosts in an honorific way. The text asks the ghosts or the spirits to take pity on us as a people and restore us to life because I was thinking of how we have lost our way. We are so entrenched in the material world that we need to understand again that our relationships are far more expansive than just to the material world.

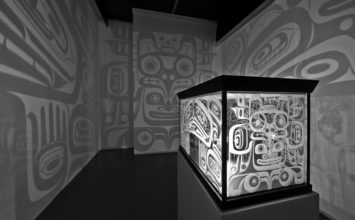

My other work, The Container for Souls, is a far more subtle work. There is a belief that the soul or the spirit is like a shadow, and I created a piece that juxtaposes a lit glass box, which has a very strong physical presence, with the shadows cast out onto the walls, which give a sense of ephemerality. This work was more deeply embedded in a conversation around the valuing of Pacific Northwest Coast artworks—that they have, by the outside world, been valued for their presence as objects. But it is more our ideas and ways of thinking that are valuable, and we need to be looking beyond the object to the ideas and the concepts.

It was seen that our cultures were dying or fading away, so anthropologists came in and collected our people’s stories and material culture, removed them from the communities, and brought them to institutions all across North America as far away as New York City. It is a really important process to intellectually repatriate that back to the community. This is an actual process we are engaged in. We physically go to locations such as the American Museum of Natural History in New York and access these objects and handle, photograph, and document them with the intention of bringing that information back to the community to share it and integrate that understanding back into its source of origin.

Think back to “take pity on us and restore us to life:” these objects we research have a life to them. It was interesting to physically hold an object that you know your own ancestors had created and used over a hundred years ago. So when I handle them myself today, there is something that goes far beyond just the object itself. In a way those vaults at the American Museum of Natural History are filled with ghosts.

Liz Park

Repatriation of ideas and immaterial things seems to relate to the world of ghosts. The text you wrote is both a prayer and a statement of intent, declaring that you are repatriating the ideas and stories that have been divorced from the objects.

MN

My mom and my grandparents were put into residential school systems with the very purpose of eradicating those ideas from their minds. At times, I feel as if I have been personally haunted by my mother’s story, by my grandparents’ stories of how these things were meant to be erased, and I think, “We must remember!”

Now we are forced to go out to institutions to recover this information. But it is not one hundred percent a bad thing. It is actually a very helpful thing, paying homage to my grandparents and to my direct ancestors whose lands we still exist within, and their spirit is still there. There is energy in these objects and there is always the hope that maybe I can understand them better by seeing them in person. But the real value is not in the objects themselves—it is in the ideas, the histories, and the connections behind them.

LP

All these immaterial things you speak about are captured in the most elegant use of materials in your work. The glass box, for instance, is a container that is incredibly porous and hard at the same time, transmitting light and shadows. The light and shadows in turn create images and narrate stories. We see from your more recent interest in rivers that water is yet another elemental material you explore. Can you speak a bit about this exploration?

MN

Our village is beside a river. Our people, the Dzawada̱’enux̱w, have lived beside this river for thousands of years. So this river has been a constant. I never knew my grandparents; both of them died tragically before I was born. But I think about how they walked beside the same river I walk beside. That river has seen everything and contains within it all the knowledge of that land for thousands of years. So it connects me to all that has come before, to the point of our origin, because our origin stories tell of how we came to that place. It also connects me to the future, and that is what I’ve really been fighting for politically: for us as an indigenous nation, for our continued existence within that landscape, because we have such an in-depth spiritual relation to that land.

The very essence of my ancestors exists within that landscape. They were buried there. They are a part of that land in the same way that my own body will become part of it eventually and hopefully my children, but I have to fight for that. There is a philosophy in place now that would have us separate from that land and sell it as an object of value when, to us, its true value is spiritual.

The river has consistency, but it is also inconsistent in that it rises and falls. Sometimes the river is very low and sometimes it is very high, and our relationship to it shifts. In 2010 the river flooded so badly that our village was under nine to ten feet of water, and the entire village had to be evacuated by helicopter. This happened because of the culmination of global warming that is melting the glacier that feeds the river and one hundred years of forestry that has destabilized the environment.

LP

From the way you describe how the river connects you to both your grandparents and children, it seems that there is a temporal dimension to the river. I wonder, is there a connection between the river and ghosts? In flowing through multiple temporalities, does the river create a connection to other worlds?

MN

We see the river as a living thing that has borne witness to our lives and to the lives of all those before us. What’s scary is that now we can actually dam rivers, stop their flow, and eradicate them altogether if we choose. Humankind now has the audacity to think that that is a good idea. The value of the river goes beyond our mapping of it as a resource. In the minds of the Dzawada̱’enux̱w or any people who have lived alongside a river for a long period of time, the river is an animate being, but that belief system is being crushed by a predominating system coming from the outside world that says it’s just water…

LP

Rivers are fundamental to life. As a source of fresh water, our lives actually depend on them. Fresh water is declared a universal human right. Yet it is valued in such an unimaginative way, in our capitalist world. And this kind of valuation is not only limiting, but catastrophic to us.

MN

Catastrophic is the right word. We’re in a fight. The real impetus behind my artworks is my desire to create some kind of platform to speak from, and to manifest these ideas, because we’re in a fight every day within our lands. Even amongst our own people, we’re being brainwashed to think of things only for their dollar value.

The sad thing is that even for myself, the pull of the outside world was so strong that I didn’t go home for years. When I go home, I realize what an impact it has on me because I understand, within my very body, how connected we are, and how sad and tragic it is for us to walk away from that. These intangible things have such impact; there has to be a way to create tangible things that help us to understand. And that is the process of creating artworks so that maybe other people can experience it too.

LP

You may be pulled to other parts of the world to create art, but that’s also a way to connect to others. And that’s what artists do: they work with materials in such a way that they give form to things that are invisible.