THE ARTIST

as

ARCHITECT SURGEON

Buzz Spector

It’s not useful to mislabel Brian Dettmer’s artistic method as “whittling,” although the paring away of pages through the use of blades is visible in much of his work. It’s more to the point, really, to imagine Dettmer, as he prepares for the task of book-altering, thumbing through the pages of an old encyclopedia or dictionary (to name two of his favored reference categories) with the attitude of a modern-day Vesalius, drawing opened up and disarticulated bodies as material to be read. There is a quasi-surgical aspect to Dettmer’s art. Whether on books or in a variety of related objects, including maps, record album covers and sleeves, or found audiocassette tapes, Dettmer operates on his chosen elements, making new bodies from pieces of the old.

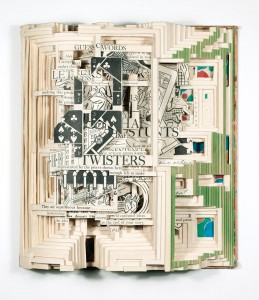

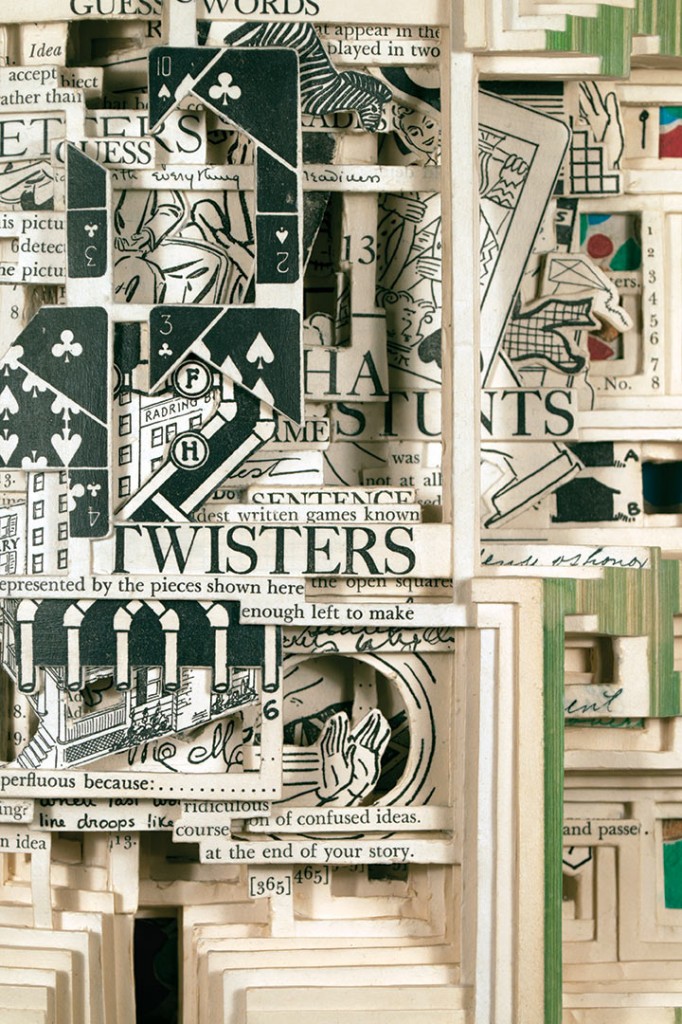

THE BIG FUN BOOK, 2012

Hardcover book, acrylic varnish

10¼” × 9¼” × 2¼”

Courtesy of the Artist and Saltworks

Collection of Larry Kennedy

“Elemental,” Dettmer’s exhibit at Haverford College, features a number of the artist’s signature altered book works, but also includes two large-scale works that expand the scope of his artistic interests. The first of these, Altered States, 2012, is a wall installation of fifty small state flag collages, each framed in white painted wood and so arranged as to make an abstracted map of the United States. Each collage incorporates a reproduction of an individual state flag, cut up and reassembled to form visual commentary on its politics. In turns comic and critical, Altered States maps political and satirical as well as geographical terrain. The other new work, Chaos, 2012, is a large-scale screenprint whose circular image is comprised of a matrix of usages of its titular word, radiating outward in Dettmer’s unique schematic. The “chaos” at the center becomes the starting point for reading both the word’s evocative linguistic endlessness and the compensatory visual logic of Dettmer’s graphic armature.

Dettmer practices excision-as-composition in his book works, cutting away the dross from his selected tomes in order to free words and pictures that become Dettmer’s own for reading. Dettmer’s alterations of individual volumes rely to some extent on chance. He more often employs his knives to cut away portions of several—or dozens—of pages at once than to trim away material from an individual page. In talking with the artist about this process he has acknowledged that some measure of happy accident guides his work; unanticipated images or words revealed by the action of the blade inspire changes of incisive direction. A few hundred books along this studio path, however, have enhanced Dettmer’s awareness of such likelihood, and he carves away at one text block or another ever cognizant of the potential narrative shift that may come from the next removal.

THE BIG FUN BOOK, 2012

Hardcover book, acrylic varnish

10¼” × 9¼” × 2¼”

Courtesy of the Artist and Saltworks

Collection of Larry Kennedy

Reading the text/image interactions in Dettmer’s altered books is an experience foreshadowed by such aleatory predecessors as the Dadaist Tristan Tzara, who in the 1920s pulled individual words cut from printed books (in his case Shakespeare’s Sonnets) out of a bag to make poems, or Brion Gysin and William Burroughs’s “cut-ups” of the 1950s. Unlike them, however, Dettmer keeps the book itself in play, as architectural artifact within which one searches for the reading he has crafted. In this regard Dettmer invites comparison with Joseph Cornell as a maker of crafted interiors. Dettmer’s environments are bounded by the structural margins of the book; its spine, covers, and text block; more so than by the two-dimensional limits of its typography or pictures. Dettmer utilizes the “depth” of the book, its third dimension, to add a subtle resonance to his excavations. Poring over these works, one becomes aware that even the shallow space within the aperture “framed” by what’s left of the book’s cover and the deepest penetration of its pages are agents in assessing the meaning of what Dettmer has done. The erotic longing infusing Cornell’s Untitled (Penny Arcade Portrait of Lauren Bacall), 1945-46, is sensed in part by the armature framing a collaged image of the actress, as if she were regarding us from the window of a room whose door is hidden. Dettmer’s strips of language and silhouetted figures and things also retreat into the depths of their books and it is no small part of his virtuosity that he imbues different books with differing spatial aspects. Some of Dettmer’s carved interiors resemble packed storage bins or Ali Baba’s cave, others appear oddly dematerialized as if their bits of language and/or pictures were receding into a mist.

Among contemporary writers, Jonathan Safran Foer comes closest to Dettmer’s approach. In Tree of Codes, Safran Foer’s die-cut excision of Bruno Schulz’s mid-20th century novel, The Street of Crocodiles, he cuts away portions of Schulz’s narrative to tell his own story, both a part of and estranged from that of the original. The succession of cutaway word-bearing strips in Safran Foer’s book (object) have something in common, at least visually, with Dettmer’s endeavor, although the publication of Tree of Codes was made possible by printing the appropriated text of Schulz’s original only on recto pages. The British critic, Michael Faber, in an online review of Safran Foer in London’s The Guardian, admitted to reading Tree of Codes by “turning the pages ever-so-gingerly and inserting a blank sheet behind each so as not to be distracted by the layers beneath,” but the necessary inviolability of Dettmer’s work—his are, after all, artworks rather than editioned publications—makes his alterations into matters of space as well as sequence, incorporating the emptied portions of their pages as much as what remains in service to their meditations on language, image, time, and structure.

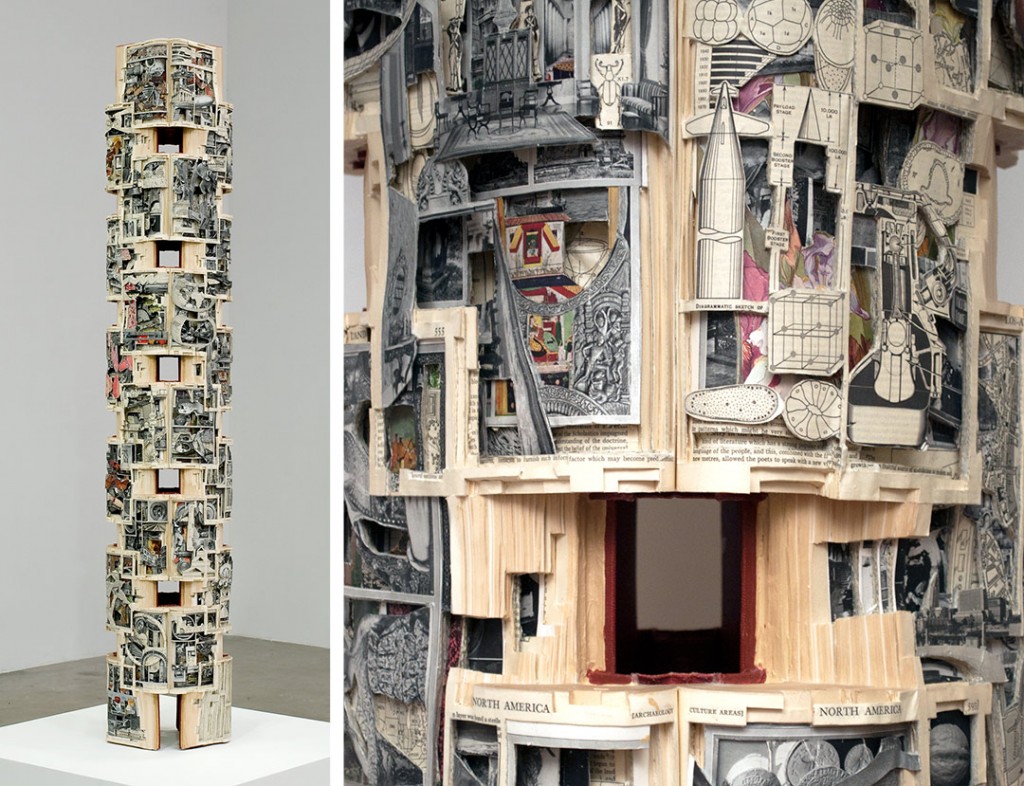

TOWER I (BRITANNICA), 2012

Hardcover books, acrylic varnish, wooden base

41½” × 51″, 41½” × 40″, 41½” × 51″ (tryptich)

The precarious stack of open, excised, and interlocking encyclopedia volumes comprising Tower I (Britannica), 2012, may make it the preeminent artifact of Dettmer’s book altering. Simultaneously Vitruvian architecture and body, its passages, entryways, vestibules, and arcades are also so many orifices, joints, or musculature. Whether Tower of Babel or Frankenstein’s Monster is the simile of choice for its viewers, the thing itself seems more frail than looming. Tower I threatens to fall at the slightest touch, an apt circumstance for the physical books of which it is made, themselves receding from view in the imponderably mediated future we all face ahead.