Ernest Larsen

“In what sense, if any, can two form a collective?”—A Political Romance (1975)

The answer to that question is still up for grabs.

All hands agree that the unanticipated appearance of the Zapatistas on the world stage in historical conjunction with the Battle for Seattle marks the beginning of the contemporary resurgence of anarchist practice. Suddenly, the old reproach from the left, that whatever anarchists were still around (time-warped holdovers from the ’60s, for the most part) could safely be left to play in their utopian sandbox, was now null and void. That paint-chipped sandbox started to look more like a treasure trove—or was it now more properly a weapons cache?

Just to steer clear of that overdetermined battlefield, nearly the entire arsenal of anarchist practice may be comprehended in two words: direct action. A full century ago, a historical moment when anarchism was recognized as a rising force in the public sphere, the American anarchist-feminist Voltairine de Cleyre wrote, “Every person who ever had a plan to do anything, and went and did it, or who laid his plan before others, and won their co-operation to do it with him, without going to external authorities to please do the thing for them, was a direct actionist. All co-operative experiments are essentially direct action.” The correlation between direct action and cooperation that de Cleyre points to is in the anarchist view what could be called anthropolitical, in a sense established to some degree by Clastres’ Society Against the State: “It is precisely in order to exorcise the possibility of . . . the law that establishes and guarantees inequality—that primitive law functions as it does; it stands opposed to the law of the State.”

“The boys, resting for the evening shift, sat up as I rushed into the room, newspaper clutched in my hand. ‘What has happened? You look terrible!” I handed them the paper. Sasha was the first on his feet. ‘Homestead! I must go to Homestead!’ I flung my arms around him, crying out his name. I, too, would go.”—Emma Goldman, Living My Life, quoted in A Political Romance.

Sherry Millner and I had been engaged in cooperative experiments in direct action even before we met in 1969 at Ed Sanders’ Peace Eye Bookstore on Avenue A (across the street from the Psychedelicatessen) on the same Lower East Side from which Sasha Berkman set out in 1892 to perform an attentat against the black-hearted industrialist Henry Clay Frick, who’d called in the Pinkertons to break the Homestead strike. We met as conscious anarchists (I was a draft resister active in the Resistance and she was a member of Anarchos, the affinity group centered around Murray Bookchin) who also happened to think of ourselves as artists. We both took what seemed like an obvious indivisibility of anarchist/artist as an inestimable advantage. By some stroke of cosmic luck, we weren’t stuck in the otherwise interminable to and fro of privileging first radical politics then art, with all the attendant if regrettable hand-wringing that often accompanies such a double bind. Much more common at that moment was the overestimation of political action as opposed to ineffectual culture, whereas we were both under the sway of another aspect of the anarchist ethic: Rather than renunciation or sacrifice (either-or), we (insolently or not) assumed the salubrious quality of the both-and, one book Kierkegaard never got around to writing.

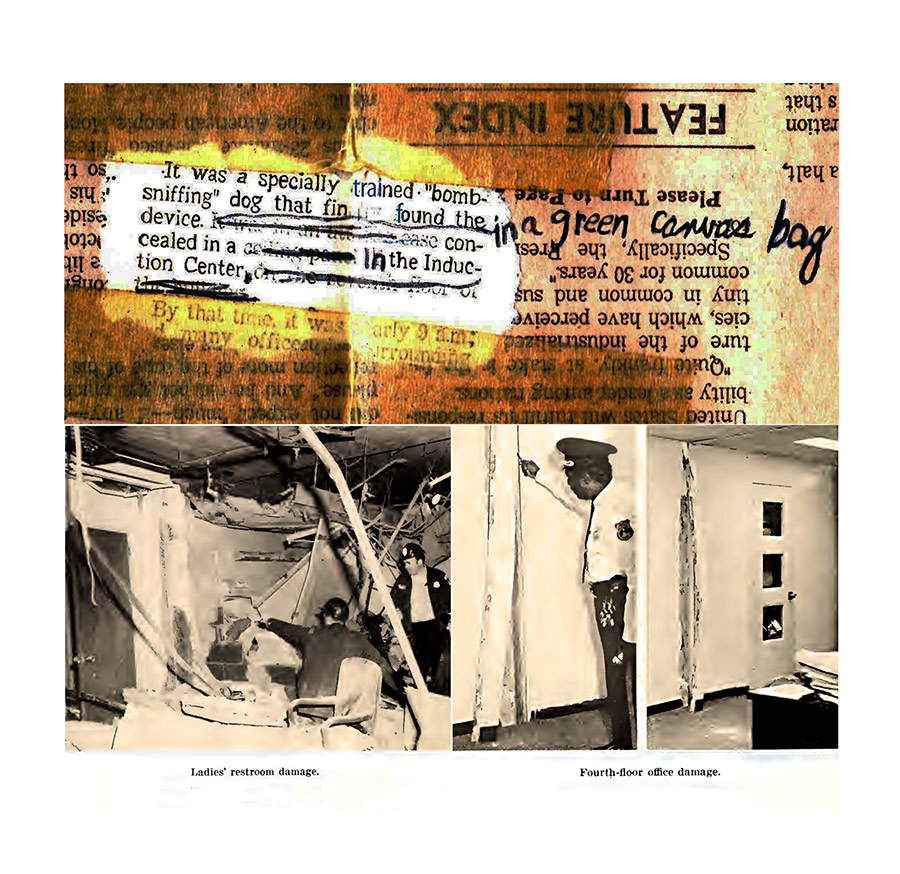

Most of our collaborative works, beginning with the performance A Political Romance, an extrapolation of the Weather Underground bombing of the U.S. State Department on January 29, 1975, are rooted in controversial historical situations or contradictory social conditions. That performance began with Sherry saying, mischievously enough, “Before we begin, I’d like to give a critique of this performance,” and she read aloud a passage from The Society of the Spectacle (the unauthorized translation, no copyright, no rights reserved, 2nd edition, 1973, Black & Red), which begins, “The alienation of the spectator to the profit of the contemplated object. . . .”

Even in our first collaboration, we knew that only two voices, two viewpoints, were by no means nearly enough. Jettisoning the eternally seductive false demon of originality, we sought to multiply both voices and forms, which amounted to the collective work of dozens of contributors, each providing at least a fragment, a sentence, an image, a history, a moment, deliberately mismatched, with jagged edges, torn or half-buried. The half-hour performance, using a silent videotape; slide projections of text (documentary, quoted, fictional, and autobiographical); and images, audio, props, and us as performers, at once appeared to advocate and to challenge the revolutionary violence of the Weather Underground. A time clock

prominently placed was counting down moment by moment to the explosion of the dual incendiary device of the performance and the bomb. Threat and promise and gestures—we built around those performatives bits of texts from a dozen or more sources, including the recently published Weather Underground manifesto Prairie Fire, William Powell’s The Anarchist Cookbook, as well as the writings of Emma Goldman, Antonin Artaud, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Guy Debord, Raoul Vaneigem, and Lana Turner.

Only Wittgenstein knew that even the rose was armed: “The rose has teeth in the mouth of a cow.” We were interested in examining or perhaps in simultaneously testing and contesting the relevance of political violence in mid-seventies U.S. How were we implicated in it? The

upper-class arrogance and simultaneous self-abnegation of the Weather Underground we set alongside other passions, I think. Our own relationship was mercurial then: In the same day we’d be out fooling around in the desert sun and then fighting bitterly about nothing at all and everything and then some in the car on the drive back from the desert. That burning quality ran through the performance from beginning to end. There was something scary about its intransigence to some people in the audience, as if we were capable of sudden violence or at least of a heedless leap into crime.

True, we were so poor for awhile that we were stealing food from the supermarket. For a few weeks we slept in a tent in the state park in the Angeles National Forest. There were invigorating rumors of marauding serial murderers in the vicinity, not to mention the occasional over-friendly bear. I worked for a time as a casual daylaborer, then as a drink waiter at a squalid club named Starwood until I was fired. We wouldn’t starve so long as we could steal, like Paul Muni in the final shot of I Was a Fugitive From a Chain Gang. How do you live? I steal. In other words, for the performance we came by our mostly comic intimacy with violence honestly.

In this sense, and only this sense, temporary poverty enriched us. We figured out how to accelerate and how to celebrate instability, the chemical suspension of all potential existence, under the rule of monopoly capitalism.

It’s fair to say that we considered the work (art, film, writing) as an indirect (i.e. mediated) form of direct action, a challenge to, if not an outright attack on, well-behaved contemporary culture. But it is possible to be more specific about the political potential of an indirect direct action. Even work that functions as no more than a model or representation is also, when experienced or encountered, an enactment with the implicit potential to alter not merely consciousness but to contribute decisively—especially at explosive moments—to the alteration of future collaborative or collective behavior. Or so we thought. Such work, it seemed, must aim at intervention, that is, to cause a rupture, not simply a change in consciousness. As a result, we applied more imagination to technique and form than to the initiating subject matter, the pre-text. In addition to the Weather Underground bombing, we examined the seventies vogue in disaster movies set against the disaster of everyday life, Lee Harvey Oswald as a contestant on the TV show To Tell the Truth (“Will the real Lee Harvey Oswald please stand up”), the class politics of pregnancy in the U.S. as constituted through Sherry’s own pregnancy, a moralizing educational documentary on shoplifting reconfigured as a training film on the same subject (property is theft)—these early projects enacted in form the rupture between what is and what could be in the public sphere. Or, to be more accurate: what couldn’t be.

There was a sustaining clue (or a hundred of them) in this working method, which turned the fledgling strategy of intervention into an experimental principle, into the permanently unstable relations between form and content, into a growing range of strategic guesses and even understandings of how audiences can be provoked and activated, into the displacement of conventional venues into experimental spaces and the progressive movement into unconventional venues (streets, restaurants, malls, social centers, etc.), into the insistence on including reception (discussion, argument) within the domain of exhibition (and distribution) and critical discourse (and its construction). All of this, singly and collectively and as constituent elements of a process, potentially nudges or slams mere perception toward active moments of potential historical change.