War and Society

Paul Jakov Smith

Collectively, we inhabit a world engulfed in wars, including (in Afghanistan) the longest war in American history. As members of an institution founded by and dedicated to Quaker values, we are made mindful of war through our dedication to peace. Yet few of us on campus have experienced war firsthand, or even come in contact with those who have. This isolation from one of the most ubiquitous phenomena of our time mirrors the larger divide in American society, whose military is staffed by less than one-half of one percent of our population, half of whom hail from just five states. According to the Los Angeles Times of 2015,

Most of the country has experienced little, if any, personal impact from the longest era of war in U.S. history. But those in uniform have seen their lives upended by repeated deployments to war zones, felt the pain of seeing family members and comrades killed and maimed, and endured psychological trauma that many will carry forever, often invisible to their civilian neighbors. 1

To the ordeal of our traumatized and wounded warriors must be added the unimaginable suffering and dislocation of the civilian populations of war-torn countries around the world, suffering that we see on television but are far removed from in person.

It is this disjunction between ubiquity and isolation that has prompted six faculty members and a postdoctoral fellow to come together under the auspices of the Hurford Center for the Arts and Humanities to learn more about the intersection of war and society. Our participants bring to the seminar expertise in jihad in the Middle East; wars in Africa, China, and Vietnam; the literature of the Great War; and Quaker perspectives on peace and war. But only one of us has actually served in the military, and at that, as an intelligence officer for another country removed from the field of battle. So our first inclination has been to do what we’re trained for: to read about the global and historical experience of war.

Our first reading, a sociological inquiry into the nature of war as “a foremost social fact,” pushed against the inclination to condemn war outright by urging readers to acknowledge that “war is responsible for some of our highest achievements and deepest held values as a society,” capable of calling forth exceptional manifestations of honor, courage, and selflessness. As Miguel A. Centeno and Elaine Enriquez point out, “despite the anti-bellic clamor of the past century, there is arguably a much longer literature extolling war as

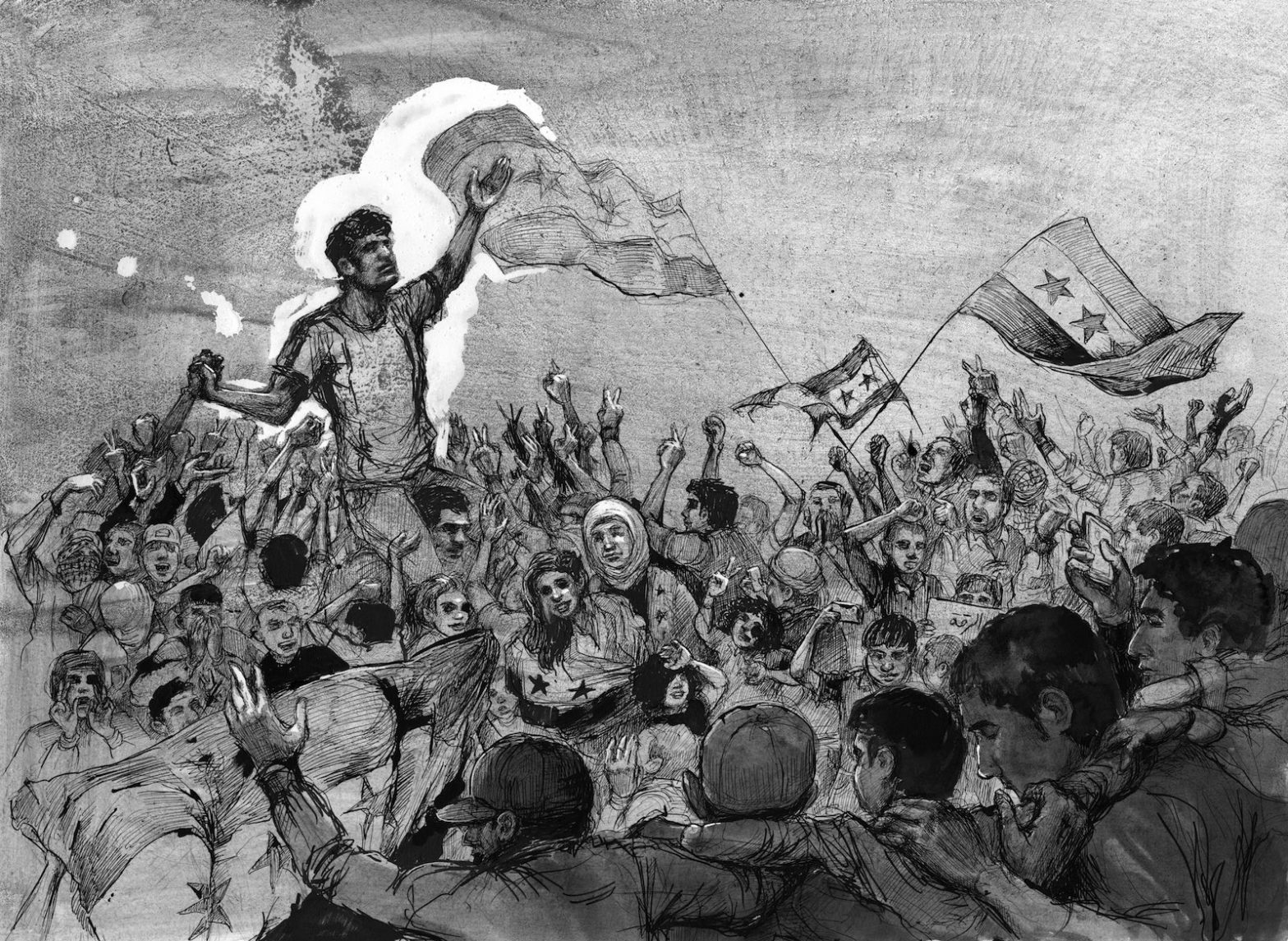

the righteous acts of the chosen.”2 This celebration of righteous courage even infuses the anti-war memoir by Marwan Hisham that has inspired the present exhibition. Of the anti-Bashar demonstration in Raqqa, 2011, that opens his tale, Hisham writes as follows:

I see a gas canister on the ground. It leaks the same foul stuff that’s making water stream from [his friend] Tarek’s eyes. I pick it up from the back end so that it won’t burn me. My hand screams anyway. I throw it toward the line of riot cops. I don’t know where it goes, but I grin anyway, exultant.

It is my first protest.

Fear is dead.

If a bullet hits me now, I’ll feel no pain.3

But while battle may inspire individual acts of courage, the adrenaline-suffused passions inspired by battle inevitably spawn death and destruction that is not only heartbreaking but often counterproductive. Military theorists from early on, in many cultures, sought to restrain the chaos and wanton destructiveness of war with reason and rules. We see this in the 5th-century BCE Art of War attributed to Sunzi (孫子兵法), with its encouragement to win wars without fighting battles. At around the same time but a continent away, that same emphasis on the utility of restraint characterized Diodotus’s speech to the Athenians advocating mercy to the enemy city of Mytilene, not on the grounds of justice but rather self-interest.4 The ongoing attempt to minimize collateral harm in order to maximize effectiveness and moral legitimacy is reflected in another of our readings, this one from two-and-a-half millennia later. In the chapter on “Leadership and Ethics for Counterinsurgency,” The U.S. Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual of 2006 states that:

Typically more force reduces risk in the short term. But American military values obligate Soldiers and Marines to accomplish their missions while taking measures to limit the destruction caused during military operations, particularly in terms of collateral harm to noncombatants. It is wrong to harm innocents, regardless of their citizenship.5

Beyond sampling how philosophers and strategists have viewed war, we have sought to acknowledge the gap between civilians and soldiers by attempting to better understand the experiences of men and women warriors. Few wars have been as eloquently rendered on the page as the Great War, whose literature our seminar comrade Steve Finley has studied and taught for some thirty years. Steve enriched our understanding of Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of an Infantry Officer by directing us to Sassoon’s poems that capture the folly and pity of war. The terror of a soldier about to be sent into battle is depicted in this excerpt from “Counter-Attack”:

He crouched and flinched, dizzy with galloping fear, Sick for escape, – loathing the strangled horror And butchered, frantic gestures of the dead.

An officer came blundering down the trench: ‘Stand-to and man the first-step!’ On he went . . . Gasping and bawling, ‘Fire-step . . . counter-attack!’ Then the haze lifted. Bombing on the right Down the old sap: machine-guns on the left; And stumbling figures looming out in front. ‘O Christ, they’re coming at us!’ Bullets spat, And he remembered his rifle . . . rapid fire . . . And started blazing wildly . . . then a bang Crumpled and spun him sideways, knocked him out To grunt and wriggle: none heeded him; he choked And fought the flapping veils of smothering gloom, Lost in a blurred confusion of yells and groans . . . Down, and down, and down, he sank and drowned, Bleeding to death. The counter-attack had failed.6

In addition to readings, we have had the benefit of hearing from two warriors themselves. Before becoming Headmaster of the Haverford School, John Nagl served with distinction as commander of a tank platoon in the 1991 Persian Gulf War and again as third in command of a tank battalion in the Iraq War in 2004.7 As a West Point graduate (1988), Rhodes scholar, and Oxford Ph.D., Nagl acquired scholarly expertise in fighting insurgencies that was put to practical use when his mentor David Petraeus directed him to compile The U.S. Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual.8 Nagl tells great war stories, but from him we also got a view of war from the top of the policy-making pyramid, as military men for so the policymakers all seemed to be) did their best to counteract the folly of civilian superiors who (as they saw it) were mismanaging an ill-considered war.

From the rarified vantage-point of Lt. Colonel Nagl we were brought down to earth by the experiences of health care specialist/combat medic Jenny Pacanowski, who was navigating her military ambulance throughout the Sunni Triangle at exactly the same time that Nagl was directing his tanks. From Pacanowski we learned about the steeliness and psychological gyrations needed to fend off the variety of humiliations heaped on women in the military. But we learned even more about the torments of PTSD that afflict so many military women and men. Now a lecturer, poet, and director of women’s empowerment and veteran reintegration programs, Pacanowski deploys and teaches writing as a way to keep the demons of PTSD at bay. But those demons are relentless, as we see in this excerpt from her poem “Parade”:

I was missed by IEDs, bullets, mortars, RPGs. Is it luck?

Was it training?

Was it GOD?

Was it the Devil?

Why did I survive only to come home to a war with an invisible enemy in my own skin? I live in a dream called my life. Where the good things don’t seem real or sustainable.

I live in the nightmares of the past called Iraq and PTSD that never run out of fuel.

Is it better to be a dead hero?

Or a living fucked up, addicted, crazy veteran?9

This spring we will have a chance to learn firsthand about living through the chaos of war from two survivors. Our first guide is Le Ly Hayslip, whose experiences as a peasant girl recruited into the Viet Cong are memorably recounted in her book When Heaven and Earth Changed Places: A Vietnamese Woman’s Journey from War to Peace.10 As founder of the “East Meets West Foundation” and the “Global Village Foundation,” Hayslip works both for the reconstruction of her home country of Vietnam and the emotional healing of American soldiers who fought there.

And that brings us to the present exhibition. In a world buffeted by brutal wars, few are more horrific than the internationalized Syrian civil war that is now entering its eighth year. We in the Hurford Center for the Arts and Humanities Faculty Seminar, along with the larger community in and beyond Haverford, are humbled to bear witness to the horrors of that war through the memories of Marwan Hisham and their transformation into art by Molly Crabapple.

Paul Jakov Smith

Convener, HCAH Faculty Seminar on War and Society, AY 2018–19

Footnotes

- David Zucchino and David S. Cloud, “U.S. military and civilians are increasingly divided,” Los Angeles Times May 24, 2015 (https://www.latimes.com/nation/ la-na-warrior-main-20150524-story.html).

↩ - Miguel A. Centeno and Elaine Enriquez, War and Society (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2016), 4–5. ↩

- Marwan Hisham and Molly Crabapple, Brothers of the Gun: A Memoir of the Syrian War (New York: One World, 2018), 3. ↩

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, Book 3, excerpted in Gregory M. Reichberg, Henrik Syse, and Endre Begby, eds., The Ethics of War: Classic and Contemporary Readings (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2006), 9–11. This hefty reader offers a rich sampling of Western debates about just and unjust wars and arguments for subjecting war to clearly defined rules. Our seminar was frustrated at the lack of a similar reader focusing on non-Western traditions, although scholarly overviews are provided in The Ethics of War in Asian Civilizations: A Comparative Perspective, ed. by Torkel Brekke (London: Routledge, 2006). ↩

- David H. Petraeus and James F. Amos, The U.S. Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual (Kissimmee, FL: Signalman, 2006), republished by the University of Chicago Press (2007), 245. ↩

- Anthologized in The Penguin Book of First World War Poetry, ed. by Jon Silkin (London: Penguin, 1979), 129–30. ↩

- https://www.nytimes.com/2004/01/11/magazine/ professor-nagl-s-war.html. ↩

- In his Foreword to the University of Chicago edition of the Field Manual Dr. Nagl explains its evolution and continuing importance, one of several useful additions to the original 2006 edition. ↩

- http://www.warriorwriters.org/artists/jenny.html, part of the Warrior Writers website (http://www.warriorwriters.org/index.html). ↩

- Le Ly Hayslip with Jay Wurts, When Heaven and Earth Changed Places (New York: Doubleday, 1989). ↩

Banner: A Protest in 2011, 2017, pen and ink on paper. 22 1/6 x 29 ¾ inches. © Molly Crabapple. Image courtesy the artist.