Hee Sook Kim: Hybrid Parallels

Jonathan Goodman

HEE SOOK KIM HAS LONG DEMONSTRATED AN AFFINITY FOR HYBRID IDENTITIES; as a woman who grew up in Korea and who has taught for more than a decade at Haverford College in the suburbs of Philadelphia, she has internalized experience from two very different places and cultures. Kim, a painter and printmaker, has evolved a style that greets the ephemeral, evanescent traces of her training as an Asian art student, as well as the insights she gained as an artist working for more than a decade in New York. Now in mid-career, and as this exhibition amply shows, Kim has come full circle, embracing a vernacular that ties her firmly to Asian art traditions. Her work, with its decorative patterns and exquisite designs, invites her audience to view the traces of her long and varied journey as a Korean, an emigrant, and a woman. At the same time, the work is not only or utterly Asian. Using her sensibility with unusual skill, Kim attaches care and energy to her lyric compositions, creating clever, conversational echoes that build a dialogue between cultures and their differing attitudes toward art.

Yet Kim’s work is not only a delicate kind of poetry; her attentions do not appear as faded recognitions of an earlier epoch. Instead, she works out patterned abstract elements in her etchings and paintings, which frequently include realistic renderings of animals. These pictures are sharply current. The imagery’s design is straightforwardly direct, forming contemporary abstractions that call attention to the historical legacy of Korean textiles whose muted presence often serves as a ground for the artist’s meticulous presentation. Kim interweaves classical and modernist stances with an ease that is inspiring, leaving her viewers with a sense of interior calm and even joy taken from everyday life. While Kim’s art and imagery do look to the past, she is very much a contemporary artist. Her interest in cultural history anchors images at home both in the past and the present.

Kim salvages an ancient aesthetic, rendering its emotive memory alive and relevant within current artistic forms. The ties that remain remind us that art can be powerful because it is, at least on one level, ahistorical—all at once Kim’s insights seem current and universal because they derive from historical specificities. She offers her audience the best of historical awareness, coupled with a remarkable feeling for contemporary issues and interest. In conversation, Kim has made it clear that she intends to return to Korean matters as a simple demonstration of her complex identity—she is an Asian artist making her way in a Western world.

Indeed, Kim has lived here long enough to comprehend the American emphasis on individuality and even rebellion, its penchant for a radical change in both idea and image. But as an Asian artist Kim places craft at the center of her art, a masterful combination of skill, thought, and emotion. While she frames within her works an American history of painting and graphic design, she is also open to an increasingly globalized perspective. Like other artists, including Lee Bul and Shegeku Kubota, Kim experiments in an eclectic and international field of source materials. She acknowledges a worldwide development across cultures in which the nationalism of a particular artist is subsumed by a style that is inherently wide-ranging. Yet her work may also raise a question for some audiences—when does eclecticism become appropriation and appropriation cultural theft? As important as this query may be in terms of cultural ethics, it is a bit peripheral in relation to Kim’s art, which has the uncanny ability to be itself—that is, personal to the artist but also representative of the many cultures she has encountered. In this sense, she has various precedents in painting (though not all of them were considered successful): one remembers, for example, the cursive exuberance of Franz Kline, the major abstract expressionist whom I have heard Chinese artists describe as a great painter but a terrible calligrapher.

So Kim can choose from an array of possibilities with global implications: both Asian and, to a lesser degree, Western. Her etchings, lithographs, and silkscreens tread lightly over a path that has been established for some time—she belongs to an Asian expressiveness in America that has been vital long enough to have a history, and thus an honesty, of its own. I feel more and more certain that artists like Kim will triumph in their psychic acquisitions of culture; the key lies in the integrity of their practice, which must align with the particular past(s) of the artist, as well as their unique lived experiences. It is possible for Kim to remain Asian because her tradition demonstrates stylistic effects that are parallel in their hybridity; the hard part is getting the combinations to work visually in new ways that also do justice to the older vernacular. One of the best things about Kim’s art is that she refuses to submit to a cultural reading that would casually situate her in a stance indicative of one inheritance alone.

At the same time, of course, Kim’s strongest allegiance is to her sense of herself as a specifically Korean artist. Even when her paintings deliberately conjure an American trope, as happens in some of her more expressive abstractions, it is difficult to separate that attribute from the specific matrix of Korean art. To recognize the both/and is to experience imperial American culture from a point of view that confidently cites traditions of art in the States as useful tools rather than as pedigrees of authenticity. The subtle critique is especially important given often facile misreadings of Asian and Asian-American art within popular American culture. When some American viewers assert that they are seeking levels of mystical understanding in an embrace of “East Asian” culture, they are often merely recycling the broken clichés of a colonial mindset.

But this state of affairs isn’t new. Other artists from the West have appropriated Asian styles in ways that have resulted in a heightened creativity, just as Kim has given the nod to certain Western stylistics that she makes use of to support her own, Asian, ends. We can go back to Mark Tobey, the expressionist painter active through much of the start and middle of the 20th century; he lived in Japan for a number of years, and his curling, white brushstrokes refer to Asian calligraphy in a way that gracefully recognizes Far Eastern art and acts as a precursor of the slightly later abstract expressionists. More recently, in American literature, the poet Gary Snyder and his ongoing interest in Buddhism strongly influenced the environmentalist poetic tradition. I mention these artists because they demonstrate the West’s continuing taste for things Asian, even as we know that such an interest can veer toward mere artifice and superficiality. In Kim’s art, we find a personal journey that is also an aesthetic one, in which Western art lightly but credibly shapes idea and image—even when it is from a distance.

Sometimes such cultural poaching will show the artist to understand only superficially the implications of his or her chosen inheritance; and sometimes that choice will be inspired, as we see in Picasso’s great work of 1907, Les demoiselles d’Avignon. Cultural eclecticism is not in any way new—in the West it has a real history lasting several generations. By the same token, it is said that China has now used oils and canvas (instead of ink and paper) for more than one hundred years. We are at a point where the importation and incorporation of stylistic effects is nearly taken for granted. If an artist can bring together disparate cultural elements, he or she can electrify the composition at hand by replacing one kind of reality with several. Doing so certainly has its dangers—when a coherence is not achieved, the picture plane loses its credibility, on both a formal and cultural level. But when a piece accomplishes a holistic vision, as we see in Kim’s work, we find as good a statement as can be made about the fractured, fragmented state of culture as it now stands in contemporary art practice.

The horizontal, or rhizomic, practice of art that Kim so wonderfully exemplifies is a far cry from the vertical idealizations of modernism. The implications of cultural borrowing are democratic in nature, for they propose that there is no longer one way of making artworks. The hard part is building a voice that successfully melds its components into something greater than random assemblage; a fusion of complementary elements into a broadly based but coherent interaction. Kim’s work quite literally becomes a palimpsest in which earlier views function as the ground for later insights. In Transformation 8, we encounter a blue ground on top of which a darker blue, flower-like series of decorations is imposed. Swirling outlines of clouds drip lines of white that run down like rain from the top to the bottom of the canvas. In the center of the composition, a glittering crane serves as a focal point of interest.

For a generation of older Americans, the presence of the drips, popularized by Pollock and echoed by the contemporary artist Pat Steir, may refract their own cultural inheritance. Yet legacies often pose problems. In reading this painting solely in light of earlier American painterly efforts, the works of abstract-expressionist artists especially, I am working against the better sense of my own caveat. This work likely references Korean classical traditions more formative for the artist than the legendary American artists whose styles are too particular, too intrinsic to themselves, to leave room for imitation. I think it is preferable to see this and other similar work by Kim as an ongoing recognition of abstraction in historical ink art, in which expressive displays often take on abstract meaning if isolated as discrete elements. Interestingly, a parallel hybridity takes place, whereby influences mimic each other without owing each other the support of an internalized precedent. It has become a cliché to cite the New York School in reference to such art, and so perhaps we can build a new legacy, in which we recognize the drips as a signifier demonstrable of Korean ink painting as well as abstract expressionism. As one might imagine, this second more difficult, reading likely expresses greater accuracy.

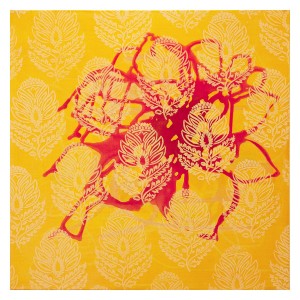

Two paintings in this show (Garden Lace 30×30-1 and Garden Lace 30×30-8) confront the reality of shared cultures in ways that also challenge the notion of monolithic Korean origins. The first is a lithograph with a light blue-green ground, on top of which we find white lace-like images covered by an organically abstract dark blue mass. Perhaps we can say that Kim’s art correlates with a magpie’s ability to take in various materials and make them useful to an overall design. Equally important, however, in our appreciation of Kim’s imagery is the respect we show toward her autonomy as an artist as she creates new possibilities for color and form on her canvas. A sister image with a yellow background, white patterned lace-like designs, and a large, entangled mass of blots and lines, only intensifies our feeling that the overlapping of imagery is both an effective visual stratagem and a metaphor in its own right, with the layers indicative of times past. It is likely that the metaphorical content of Kim’s art, the gesture to temporal accretion as visual form, is its most salient quality. The question, “How Korean is it?” does come to mind, but likely the answer must incorporate a whole that transcends an anxiety of influences.

Indeed, the metaphorical strength of Kim’s art reflects a greater, deeper reality than the sum of its parts. In today’s American culture, visual efforts often succumb to mere entertainment. Perhaps this is where the classical culture of Korea comes in; access to its historical significance lends Kim’s art a range and scope that inevitably strengthens its world of reference. In a similar way, Kim’s association with abstraction balances her aesthetic; her imagery engages in a supportive system of reference affecting both new and historical creativities. Metaphor lies at the root of innovation; the rhetorical play between image and eye draws connections powerfully new to artist and audience. Much of contemporary art no longer trusts metaphor, preferring a literalism linked to the “political sublime,” a phrase popularized by the late New York critic Arthur C. Danto. Kim does not trade in politicized and topical references; instead, she offers something else, something likely more valuable: the merger of styles that culminates in a synthesis lyrical in nature. We can call her manner of working a visual poetry that both acknowledges cultural bias and works to transcend that bias within her artistic explorations.

I have made the point that any reading of Kim’s art should acknowledge her Korean background, even when the imagery looks like American expressionism. Her work with decoration and its relations to a feminine, or specifically feminist, imagery also eludes an easy Western reading. While Kim maintains, at least in her choice of styles, a silence about feminist concerns, her art incorporates allusions to things traditionally thought to belong to women’s creative acts and sartorial choices—hence the lace we often find in her graphic work and paintings. But we must consider these predilections as mild rather than deep-seated references to Kim’s identity. There is of course the awareness, for the American viewer, that her work nods to women’s pattern painting, a feminist style that evolved mostly in New York a generation or more ago. But even that cogni-zance does not do full justice to the subtle presences in Kim’s art. Instead, the feminine that arises lingers as a conveyance of suggestions that refuses to be translated into a single cultural message. We feel the surprise of her art most powerfully when we recognize that its allusions elude easy characterization.

In most successful works of art, there is a lure of some sort—a transformation in which the imagery says more than what it actually describes. Kim’s lure is that of a world more unified in painting than what we experience in the everyday; she effectively merges a double insight, improvising from myriad aspects of visual experience. I have been at pains to emphasize how her recent paintings return to Korean sources, but it is also fair to say that the work is larger and more sweeping than its origins. It turns out that Kim’s impulse is to honor and even protect her identity by additionally embracing her American experience in works I have called hybrid parallels. She finds connections in the broad and grand tradition of modernism, which by now has become an internationally accessible language. The Spiritual Garden celebrates a moment in Kim’s career and personal trajectory in which her art can freely incorporate aspects of Western visual culture without doing damage to her hybrid sense of her-self as an artist. This achievement reflects the reality of the current art world, which is essentially diverse, fluid in its boundaries.

Kim’s vitality turns on her use of the palimpsest, which emphasizes, even as it occludes, preceding versions of imagery. Ghosts of images populate Kim’s compositions, asserting themselves indirectly—but asserting themselves nonetheless. In what may be her strongest art to date, Kim offers Paradise Between, a series of etchings that incorporates images with implicitly Buddhist affiliations. One of the most beautiful, Paradise Between VIII, consists of one complete lotus flower in the upper center of the picture, and a partial lotus flower to the left. Underneath are two rows of abstract designs in green, suggestive of botanical vitality. Undeniably, the vision is Asian and suggests that Kim is returning to her identity as a Korean woman. This is a moving choice for someone in mid-career. Yet return fails to capture this turning toward origins that occurs because Kim has internalized the Western culture to which she belongs. The notion of leaving one’s home in order to find it again is decidedly romantic. There is a truth to the idea, but Kim invites us to reimagine her home and ours as a haunting accumulation of experience, image, and practice. Classical more than expressionistic, leaning as it does on centuries of lotus symbolism, Kim’s flower harbingers a powerful moment of re-discovery.

Kim, still young as an artist, is finding her way back to precedents distilled even as they recur over time. So her images resonate backward in time, even as they command a contemporary energy. The classical impulse is not popular today, for it is seen as too conservative a stance in the shadow of modernist poet Ezra Pound’s favorite injunction: Make it new. But something else is gained by Kim’s looking back; the tradition becomes a legacy, something she can use that contextualizes her creativity in ways that gain in weight. The gravitas, then, is real. Her imagery, persisting over centuries in Asian art, augurs new work in a matrix whose contours reflect a more common consensus. It makes sense that this agreement possesses an emotional range and depth indicative of the rewards of time. One hesitates to dwell too long on the past as creative transformation; this propensity too can become overly nostalgic, to the point of sentimentality. But sentiment is not a problem in Kim’s art. Her mental strength offers a toughness of its own. It would be a mistake to imprison her within the clichés of her culture, which include the vagaries of her life as an active artist living and working in the 21st century. There is no weakness in her efforts to stay aware of the past and the future even as she creates in the present, the only moment we truly know.