What Can a Body Do? By Amanda Cachia

Introduction

[aapp]

[track title=”Amanda Cachia reads her introduction to What Can a Body Do? (09:55)” format=”mp3 ogg” lang=”en”]https://exhibits.haverford.edu/whatcanabodydo/files/2012/09/Introduction_to_What_Can_a_Body_Do[/track]

[track title=”Amanda Cachia reads the artist essay for What Can a Body Do? (29:29)” format=”mp3 ogg” lang=”en”]https://exhibits.haverford.edu/whatcanabodydo/files/2012/09/Artist_Essay_for_What_Can_a_Body_Do[/track]

[track title=”Amanda Cachia Bio (00:46)” format=”mp3 ogg” lang=”en”]https://exhibits.haverford.edu/whatcanabodydo/files/2012/09/Amanda_Cachia_Bio[/track]

[/aapp]

Disability is the attribution of corporeal deviance – not so much a property of bodies as a product of cultural rules about what bodies should be or do.1

We know nothing about a body until we know what it can do, in other words, what its affects are, how they can or cannot enter into composition with other affects, with the affects of another body, either to destroy that body or to be destroyed by it, either to exchange actions and passions with it or to join with it in composing a more powerful body. 2

In his study Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza (1990), French philosopher Gilles Deleuze famously grapples with Spinoza’s question: “What can a body do?”3 This exhibition narrows Deleuze’s query then, asking “What can a disabled body do?” What does it mean to inscribe a contemporary work of art with experiences of disability? What shapes or forms can these inscriptions take? How, precisely, can perceptions of the disabled body be liberated from binary classifications such as “normal” versus “deviant” or “ability” versus “disability” that themselves delimit bodies and constrain action? What alternative frameworks can be employed by scholars, curators, and artists in order to determine a new fate for the often stigmatized disabled identity?

In “What Can a Body Do?” Deleuze draws from two statements by seventeenth-century Dutch philosopher Baruch de Spinoza: “We do not even know what a body is capable of. . . .” and “We do not even know of what affections we are capable, nor the extent of our power.”4 In other words, we haven’t even begun to understand the potential of our own bodies! Most of us know even less about the disabled body. It is important to think about what disability does rather than simply what it is. Such reframing breaks binary constructs as it is focused on a type of concretized being-in-the-world, on the truths of living inside a disabled body. As disability bioethicist Jackie Leach Scully argues, “understanding the experience of disability from this inside is essential to inform ethical judgments about impairment.”5 Asking what the disabled body can do helps us to understand what it means to think and be through the variant body. To use a term originally developed by Michel Foucault to describe ways of knowing that are left out, the disabled experience has been a subjugated knowledge.6 But what if disability could become an epistemic resource and an embodied cognition embedded within politicized consciousness?7 Or, more simply, a way of knowing the world?

For this exhibition, nine contemporary artists, including Joseph Grigely, Christine Sun Kim, Park McArthur, Alison O’Daniel, Carmen Papalia, Laura Swanson, Chun-Shan (Sandie) Yi, Corban Walker, and Artur Zmijewski demonstrate new possibilities across a range of media by exploring bodily configurations in figurative and abstract forms. The artists invent and reframe disability, each time anew. They challenge entrenched views of disability, both positive and negative, and show that we do not yet know what bodies are, nor what bodies – all bodies – can or should do. Their work confronts dominant cultural perceptions of scale, deafness, blindness, mobility, visible and invisible body differences, as well as the negative characteristics often attributed to disabled people. These nine artists adjust and destabilize an often reductive representation of the disabled body to move toward more complex concepts of embodiment.

The notion of complex embodiment was developed by disability studies scholar Tobin Siebers, reacting to the limitations of the ideology of ability. He says:

Disability creates theories of embodiment more complex than the ideology of ability allows, and these many embodiments are each crucial to the understanding of humanity and its variations, whether physical, mental, social, or historical. The ultimate purpose of complex embodiment as theory is to give disabled people greater knowledge of and control over their bodies in situations where increased knowledge and control are possible.8

Complex embodiment argues that the perception and experience of disability are complex, nuanced, and individual. Complex embodiment also suggests that there is no one way to look at or think about experiences of disability, offering avenues of inquiry that take us down an unconventional path. In turn, categories of difference, identity, and disadvantage in relationship to disability can no longer be essentialized.

What would it mean to stretch the perceived contours of material bodies, where identity is not understood as essential but as a complex coding of experience? As Siebers has argued, “the disabled body changes the process of representation itself. Blind hands envision the faces of old acquaintances. Deaf eyes listen to public television. . . .Mouths sign autographs. . . .Could [disability studies] change body theory [and contemporary art] as usual?”9 The artists in this exhibition radically open up our expectations for encounters with the physical world and demonstrate that various subject positions can be ruptured and replaced by a complex embodiment that includes impairment as a means of illumination. They use a blend of representational and non-representational imagery, immersive environments, two-dimensional and three-dimensional objects and sculptures, performances and social practice to explore non-standard perceptual and sensory experiences. They create mixed, hybridized and invented senses – even a new language.10

The artists foreground new possibilities such as how to experience music based on the imagery of physical gestures and movement in the work of Joseph Grigely, Christine Sun Kim and Alison O’Daniel, or how sound can provide a new entry point for a walk through an urban environment in Carmen Papalia’s installation. Park McArthur’s New York City care collective complicates notions of capacity and ability in the intermingling of bodies playing roles of carer and caree. Laura Swanson and Corban Walker both destabilize common notions of scale and prejudicial associations regarding height and size by offering alternative enclosures for dwarf embodiment. In Chun-Shan (Sandie) Yi’s work, the artist challenges notions of a “complete” body by suggesting that the body can reinvent itself through new footwear and “disability fashion,” while Zmijewski’s inter-twined male and female bodies, one an amputee and the others being non-amputees, transform definitions of support and insufficiency. Within these possibilities, the artists maintain an authority and ownership over their bodies and their bodies’ experiences that rearrange, reorder and help us rethink what a body can do.

What else happens when different bodies and objects come together? What is the power of this conjunction? As suggested by Deleuze at the beginning of this essay, affect is an ontological openness and vulnerability to change in anything we might encounter. For example, Brian Massumi uses the concept of affect as though it has a “margin of manoeuvrability, where we might be able to go and what we might be able to do in every present situation.”11 Queer theorist Jasbir Puar calls affect “a site of bodily creative discombobulation and resistance.”12 The nine artists in this exhibition operate within such a margin: a space that offers resistance and yet is also filled with abundant possibilities, where there is a push for a broader politics of disabled identity.

The power of allowing the audience to encounter the multi-sensorial work in this exhibition also lies in the possibility of being destabilized by the “radical alterity of the other, in seeing his or her difference not as a threat but as a resource to question your own position in the world.”13 These affective spaces offer the profound capacity for change, evolution, transformation and movement, both literal and metaphoric, and ultimately, reap new form and restabilization. They impel us not simply to look at bodies, but to contemplate what it is to live our bodies. Ultimately, perception is not based in the information the body receives about the world, but in how the body inhabits this world. These artists teach us that what a body has the ability to be and do is open to question.

The artists

Joseph Grigely creates works that explore the failures, idiosyncrasies and ruptures of language and the dynamics of everyday communication. Grigely has been deaf since the age of ten, a factor that has shaped his work and has become a central aspect of his artistic practice. He first became known in the early 1990s for a series of works he called Conversations with the Hearing. From tabletop tableaux and intimate wall-based works to room-sized installations, these works grow from the scraps of paper and handwritten notes produced when he communicates with the hearing world – a strategy Grigely employs when he cannot read lips.

Songs Without Words is a series that explores Grigely’s interest in music, which includes recalling his own memories of music as a child and his current relationship to music as a deaf man, fascinated with the way music “looks.” This difference between how sound looks and how sound sounds is in many ways both the theme of Grigely’s life as a deaf person and the theme of his work as an artist. In Songs Without Words, an original installation of twelve pigment prints, three of which are included in this exhibition, Grigely visually represents sound via images of people singing that have been clipped from The New York Times. The newspaper captions have been removed, adding another layer of linguistic absence to the work, leaving us with an experience of these performances only through their gestures. The seemingly simple gesture of giving us what the artist calls “music with the sound turned off” foregrounds all of the often overlooked aspects of musical performance – a singer’s face contorted in the ecstasy and strain of performance, a rapt audience, the agility of hands on a piano. Grigely says of this experience:

I continue to be intrigued by watching music performances. Even without actually hearing an orchestra or a choir or a rock band, the visual nature of the performance permits one to “hear” the sound as a fiction: when you watch the bows of the violins, or the conductor, or the faces of a choir, or the wrenched-up faces of rockers, implied sounds come together in an ineffable way.14

For example, in Songs Without Words (Eartha Kitt) (2012) Kitt’s body language is a powerful portrait: her right arm raised, strong and authoritative, her mouth contorted wide open as her voice pierces a note through the microphone, fingers spread on her right hand. All these visual clues aid us in imagining how the music ricochets through Kitt’s entire body. The other images are entitled Songs Without Words (Faust) (2008) and Songs Without Words (Sekou Sundiata) (2012). Like the image of Eartha Kitt, the body language and exaggerated gestures of Faust’s female opera singer in New York City’s Central Park and the poet and performer Sekou Sundiata allude to the powerful embodiment of music in the human form.

Performance artist Christine Sun Kim also explores sonic media without the benefit of hearing. She finds how to make its presence more physical, to show greater dimensions of movement, and to establish a personal connection to the aural. Deaf from birth, Kim turned to using sound as a medium during an artist residency in Berlin in 2008, and has since developed a practice of lo-fi experimentation that aims to reappropriate sound by translating it into movement and vision through performance. While growing up, Kim perceived sound as a form of authority and without realizing it, the artist was never at ease nor in complete control of sounds she made. As she grew older, she acquired two languages, American Sign Language and English, and she became aware of her relationship to sound, at which time she began to use the term “ownership.” Kim’s reception of language is shaped by sign language interpreters, limited subtitles on television, written conversations on paper and emails. These modes have naturally led to a loss of content and a delay in communication, which greatly influences the way she perceives reality and experiences the world.

For What Can a Body Do? Kim will participate in a sound performance at the opening. The performance will be composed of field recordings of ambient sound from the Haverford College campus. Speaker drawings #1-#10 (2012) will be created from the ink- and powder-drenched quills, nails and cogs that dance across ten round wood boards to the vibrations of subwoofers and speakers beneath. Speaker drawings will then be hung up on the walls of the gallery space after Kim’s performance. Along with drumhead, subwoofers, paper, objects, and wet materials, the end results will emerge as physical and visual records of sounds.

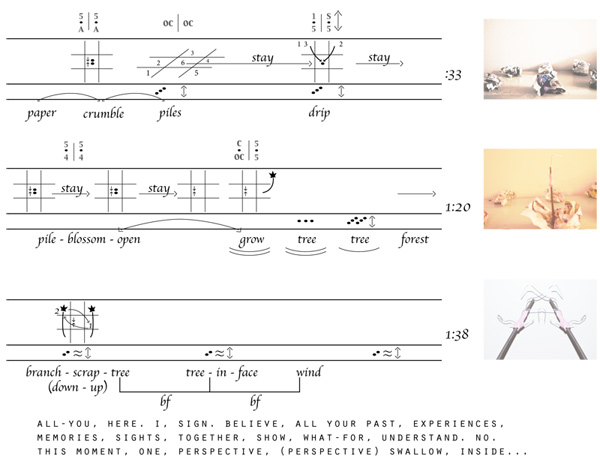

Kim’s Etudes #1, #2 and #3 were produced during the summer of 2011, when the artist appropriated notational elements from three different systems of inscription and one language – graphic notation, musical notation, and ASL “Glossing” (the coded representation of ASL) and American Sign Language (ASL) – to reinvent a new syntax and structure for her compositions. Kim has thought about how American Sign Language is full of visual nuances that are mostly shown on faces rather than through hands and how what can be seen on the face supplements what is signed by the hands.15 Like sound, ASL cannot be captured on paper; thus, Kim combines these various systems in an attempt to open up a new space of authority/ownership and rearrange hierarchies of information.

Movement and stillness – both individual and social – are starting points for Park McArthur’s interrelated series of works. Her use of temporary sculpture, works on paper, and short video present some of the ways personal mobility is tied to social and political movements. Because McArthur’s life and outlook are shaped by the physical challenges of her degenerative neuromuscular disease, working with concepts of mobility is a political and personal project.

In It’s Sorta Like a Big Hug (2012) McArthur had a friend record one of her experiences of being cared for by a collective of friends in her New York City neighborhood. The collective included a group of ten people that McArthur linked together in order to orchestrate and facilitate her bedtime routine each night of the week. To build the care collective, McArthur had to cast a wide net; six friends and two hired assistants comprised the final group.16 The care collective is a collaborative endeavor insofar as it takes seven people to cover the week’s seven days, but no individual spends time with anyother individual; some participants have never met each other.

Echoing Jasbir Puar’s notions of challenging debility, capacity and ability through a process of destabilization and then restabilization, McArthur says that processes of unraveling and restabilizing occur as individuals in the collective make themselves vulnerable to one another in the “eventness” of working to deliver each body safely from platform to platform, surface to surface. In McArthur’s relations with every individual of her care collective, she experiences the strain of someone’s body lifting her own and the strain of her own body keeping herself upright. McArthur invites viewers to think about how the care partner’s body and McArthur’s body work their mutual instability together. The artist concludes that the conditions of debility and capacity are tenuous and proximate at all times. Most importantly, this proximity opens up the possibility for us to familiarize ourselves with wide spectrums of “beingness.” She says that this is “potentially radical and definitely radically difficult.”17

As an extension to the video, McArthur has also contributed two text-based works to this exhibition. Each piece is formatted to look like unusually large wall labels, approximately 6″ wide x 36″ long, mounted on museum board, innocuously and randomly placed around the gallery. The first, titled Carried and Held (2012) is an index of all the people who have physically carried and held McArthur throughout her life. It reads “Park McArthur, with Margaret Herman, John McArthur, Nancy Herman, Emery Herman, Tina Zavitsanos, Alexandra McArthur, Amalle Dublon” and so on. The second wall label, Abstraction (2012), is about McArthur’s relationship to funding structures that continue to make her life as an artist possible – parents, family money, grants, scholarships – capitalist accumulation in the form of an abstracted, compiled list.

Alison O’Daniel works across disciplines, combining sculpture, sound baths, painting, sports/dance teams, and films with live music or sign language accompaniment, examining perceptual and emotional sensitivity between people, objects and environments. Installations, films, and instances of the performative create a biographical imaginary that shifts bodily comprehension toward a physical and tactile language of perception. Her films become a sensory experience for the viewer through a combination of subtle and pronounced transformations of narrative filmmaking and cinematic experience.

A screening of O’Daniel’s new film, Night Sky (2011) will take place during the course of the exhibition. Night Sky is a 75-minute feature-length narrative film with parallel, overlapping stories: two girls – Cleo and Jay – travel through the desert while a group of contestants compete in a current-day dance marathon. A small hula-hoop serves as a window between worlds, hovering unnoticed in the midst of the marathon contestants and simultaneously hanging in the desert air. Sound bleeds between the locations, drawing attention to a parallel series of events, while locations collapse into one another and places formerly encountered continue to announce their presence.

O’Daniel made Night Sky with a cast and crew that was half deaf and half hearing, mirroring the two main characters whose friendship seems to expand despite or because one of them is deaf and one can hear. O’Daniel is partially deaf, wears hearing aids and lipreads. She builds a visual, aural, and haptic vocabulary for making her work from experiences associated with her hearing. She says:

“The nuances of different experiences associated with deafness are incredibly inspiring to me. I’ve been interested in examining the ways that missed information, lacking details, and blank spaces might open up a transcendent relationship between the body and knowledge. Indeed, there are different ways of knowing, and Night Sky and the performances associated with it, highlight this.”18

O’Daniel then wanted to make one film where the narratives within would intersect, touch, and separate for the deaf audience and for the hearing audience. In this case disability is no longer negative or pejorative. In other words, disability doesn’t have to equal inability. O’Daniel is more interested in making a point of disability conventions and how disability is defined. So what does it mean to hear?

Night Sky can be screened either with live music or a prerecorded original score, in a theater, or outdoors in the midst of ambient sounds competing with the film, in addition to the ASL interpreter. In writing the sign score, the artist’s ASL collaborators, Lisa Reynolds, Rainy Orteca, and the artist herself were presented with a fundamental question: how do you describe music to a deaf audience? O’Daniel says:

We didn’t want to simplify the experience at all, but instead to capture the sensuality and also the physical experience of listening to a song. Through abstract descriptions of objects and nature, and rarely, but sometimes more esoteric explanations of instruments’ function and relationship to the body, we began to construct a score out of sign language that embodied the same emotional register as the music.19 (see fig. 1)

figure 1:

Alison O’Daniel, Lisa Reynolds and Rainy Orteca,

ASL score for Night Sky 2012

Ultimately, an entirely new layer of narrative is created for those who with knowledge of American Sign Language. In the screenings with sign accompaniment, there are extended moments of quiet – including a nine-minute overture of sign that the audience acclimates to – and sections where the sound of Lisa’s feet on the platform becomes as important to a hearing audience as the sound of the audience members shifting in their seats. A cough, a stomach rumbling, an air conditioner kicking in, the sound of a film’s soundtrack in a theater nearby, someone getting up to use the restroom all begin to blur with the diegetic sounds in the film, and live sign accompaniment expands for the hearing/non-signing audience to include the audience’s contributions.

The audience’s fragmented and potentially incoherent experience foregrounds assumptions about hearing impairment: O’Daniel is trying to make the ear operate as the eye does, as if comprehending information slowly, like reading subtitles (although no captions are included with the film). Thus, audiences confront their own limitations and experiences of how exclusion shapes their reading of the filmic action.

God’s Eye (2011) is a video installation utilizing and expanding upon materials from Night Sky. An eye, that of Night Sky character Deafinitely, is projected on a hanging cardboard box that shifts and sways as a disco ball rotates inside. “God’s Eye” is the Dog’s Eye – specifically, O’Daniel’s dog’s blue eye with the reflection of a window in it. The cardboard box is the original shipping container for the disco ball, a central prop that hangs above the dance marathon contestants who compete to silence in a parallel narrative within the film. The cardboard box and the disco ball inside refer to the bodies of the exhausted contestants and the two girls travelling through the desert. The disco ball – here hidden except for a moon-like sliver below – is the one constant in a dance space, a rotating beacon that continues the trance of movement.20

In Carmen Papalia’s work, relationships of trust and explorations of the senses unfold as the artist leads walks with members of the public in Blind Field Shuttle as part of his experiential social practice. This work is a non-visual walking tour where participants tour urban and rural spaces on foot. Forming a line behind Papalia, participants grab the right shoulder of the person in front of them and shut their eyes for the duration of the walk. Papalia then serves as a tour guide – passing useful information to the person behind him, who then passes it to the person behind him/her and so forth. The trip culminates in a group discussion about the experience. As a result of visual deprivation, participants are made more aware of alternative sensory perceptions such as smell, sound, and touch – so as to consider how non-visual input may serve as a productive means of experiencing place.

Produced for the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, Blind Field Shuttle – Portland, June 16 & 17, 2012 (2012) is Papalia’s first attempt to develop a non-visual document of his non-visual walking tour. The Blind Field Shuttle recordings are the product of Papalia’s collaboration with sound artist Kai Tillman. The resulting work presents a system for Papalia’s own access to the documentation of a memorable event – in this case, the two walks that he led through a park in Portland, Oregon on June 16 and 17, 2012. Each walk followed the same route through the park on the Portland State University campus, but the soundscapes that were captured are in stark contrast to one another. The document made on Saturday, June 16 depicts a group meandering through a bustling farmer’s market on a sunny afternoon, while the document made on Sunday, June 17 depicts a group strolling through a relatively quiet public park on a breezy morning. While each acoustic experience is different, sound serves as the material with which the viewer is able to develop a sense of place. The documents of these events, and the immersive sound environment in which they exist, reflect Papalia’s own experience of moving through a place without sight and introduce a way of seeing that is not reliant on the visual sense. Papalia’s intention in developing a non-visual experience, both in the walking tour itself and the documentation of that work, is not to simulate the experience of blindness for the viewer/participant, but to show one of the many overlooked entry points to experience – a gesture that works against the primacy of the visual.

From these recordings, the artist has created a site-specific installation in the gallery where the sounds are experienced in a narrow corridor as long as ten people standing single file with their arms outstretched, their hands holding the shoulders of the person in front of them. The brightness of the corridor reflects the experience of closing one’s eyes in a dimly lit room. The corridor blocks outside noise so the listeners can become immersed within the sound experience and imagine themselves as participants on the walk. Two sets of five speakers are built into the facing walls of the corridor and are positioned directly across from one another at various heights, including the height of the artist (5’ 9”), the height of the curator (4’ 3”), the average height of a woman (5’ 4”), the average height of an eight-year-old (3’ 9”), and the accessible fixture height for a wheelchair user (4’6”), reflecting the diversity of peoples’ heights on the actual walks and in society at large.

Papalia sees value in developing an experience like the Blind Field Shuttle into a gallery installation, recognizing the many ways in which society still “disables” individuals through systemic barriers, negative attitudes and exclusion.21 Papalia says:

I consider both the walking tour itself and any documentation of the project (non-visual or otherwise) as contributing to a productive model for accessibility – where people of all abilities can recognize the many entry-points to experience, and can consider each entry-point a relevant (and valuable) way of being.”22

He believes that the more models for change find their way into places where people might experience them, the better.

Laura Swanson is a Korean-American artist who addresses feelings of alterity—from having a conspicuously different body—with the creation of coping mechanisms and refuges in her fantastical dwelling spaces and staged photographs. Swanson questions the desires in wanting to look at difference. Her exploration of a space without articulated difference is materialized in her use of objects. For example, a series of anthropomorphized objects presented as pairs extends the interrogation of bodily difference in Swanson’s previous work TOGETHER together (2009).

For Swanson’s new installation Display (2012), the artist’s interest in these pairings of objects has evolved from whether people notice them because of their unassuming character and the way they blend into the environment to the very idea of displaying such objects to be noticed. Pointing to how these new pairings have become a conspicuous display, the artist has installed two stools commonly used in schools or businesses on a low platform that resembles the display of new products or cars at trade shows or in retail showrooms (Stools, 2012). Adjacent to the platform, two items of clothing rest on adult- and child-sized dress forms on wheels (Clothes, 2012).

With each pairing, the objects come in different sizes – one is short or small and the other is tall or large. This work is a double portrait: the shorter/smaller stool and article of clothing stand in for the four-foot-tall Swanson, and the taller/larger stool and article of clothing represent her six-foot-tall partner, Greg. It is important to note that despite the difference in the stature of the objects, they are all fundamentally the same. Their height makes each of them function more efficiently in a particular situation. Neither is really better than the other. However, value-ridden binaries such as tall/short, good/bad, sexual/asexual, and normal/pathological strongly inform our views of people with varying heights. Here, Swanson’s doubling of the objects defies the assignment of a so-called defective identity to one or the other because these objects are immune from such designations without context. These objects are not subject to prejudicial associations regarding size in the same way that the human body is.

Irish artist Corban Walker takes a different approach to destabilizing common notions of human scale. His work often relates to architectural scale and spatial perception, utilizing industrial materials such as steel, aluminum and glass, drawing on the aesthetics and principles of minimalism to foreground different perspectives in relation to height. Walker is four feet tall and creates his sculpture stacks in direct proportion to his body using the “Corban Rule,” a precise mathematical calculation he devised, wherein he uses his own height as the measure of his art.23 Eamonn Maxwell has explained that “given that the premise for architecture and the related design is the six-foot man, Walker has to constantly adjust to fit into what is determined as normal. . . .he is asking the viewer to please adjust to his viewpoint on the world.”24

In contrast, TV Man (2011) is an exactly life-size looped video replica of the artist standing in one place inside the monitor of a flat-screen television that is larger in scale than Walker himself. He wears dark clothing and spectacles. Here, Walker is not only adjusting and “fitting” into the built environment through this hyper-sized piece of technology, but he has inserted himself into its very frame. Through Walker’s simple, yet pointed self-portrait, he confronts the audience directly. There is no denying Walker’s unflinching gaze on the non-disabled subject. Here, he stands inside a world that has been mapped out for the “non-disabled” person. Similar to the effect of Swanson’s rotating display, the viewer is unable to escape the methods and the means in which disabled embodiment can be trapped or enclosed.

Chun-Shan (Sandie) Yi makes wearable art that addresses bodily experience and social stigma. Yi has been influenced by members of her family who, like her, have been born with variable numbers of fingers and toes for generations. Thus, Yi’s work often revolves around memories of social interactions that were focused on the appearance of her body. The process of making her adornments and objects unleashes the artist’s hidden emotions and distress. By using metals, fabrics and found objects in combination with heavily handcraft-oriented techniques like metalwork, crochet, felt-making and sewing, the artist reexamines the stereotypes and values placed on physical “deformity” and their impact on a person’s well-being. Each material and its construction method gives the artist a new voice to speak of the unspoken. For Yi, making art about her body becomes a process of embodiment.

How can the body move and how does the body feel wearing disability fashion? In Dermis Leather Footwear (2011) Yi uses latex, cork, rubber, and thread as she focuses on body reconfiguration through mapping the memories of medical and surgical intervention. Altering the purpose of conventional prosthetics and orthotics, which aim to create more-or-less standardized body form and function, the artist blends prosthetics and jewelry-making to make this unique, personalized footwear for a female friend. The wearable item is designed based on the individual’s medical experience, physical position and state of mind.25

Ultimately, this work poses the question of what it means to expect a “complete” body. Rather than reject the notion of physical alteration, Yi provides intimate and empathetic bodily adornment as a tool for remapping and engaging with a new physical terrain, one imbued with personal standards of physical comfort and self-defined ideals of beauty. Viewed as a collection of wearable works, the objects and the wearers call for a recognition of collective human experience and create space for a possible future field: Disability Fashion.

Artur Zmijewski is a Polish artist who has a long-standing interest in bodily difference. In 1998 he developed the project Oko za oko (An Eye for an Eye) consisting of a several large-format color photographs, three of which are included in What Can a Body Do? along with a video. The photographs and video depict a naked men with amputated limbs, accompanied by able-bodied people (a man and a woman) who in the staged photographs and in the film “lend” their limbs to the amputated as they stroll, climb stairs or bathe together. The naked bodies of the protagonists were assembled by the artist in complex compositions creating bodily hybrids: two-headed men, men with two pairs of arms, woman’s body as alternative leg/support etc., and at the same time the appearance of new able-bodied organisms in which the “healthy” supply the amputated with substitute limbs. The title of Zmijewski’s work recalls the antique rule of dispensing justice, but the artist is concerned not with the question of revenge but with that of possibilities.

In this work, Zmijewski poses challenging questions: Are those who help, as well as those to whom the help is offered, at risk of losing their integrity? Where lies the border between human cooperation and a symbiosis of individuals carried to excess? Is it possible at all for one person to “compensate” another for his/her impairments? Additionally, Zmijewski’s work offer a new reading of affect and how bodies move with and in composition with one another, particularly in comparison to Park McArthur’s work and to Deleuze’s thinking about bodies. Zmijewski’s protagonists become destabilized and restabilized through their physical and emotional encounters with one another. He questions here what happens in the exchange between legs, skin, hands, arms, genitals, breath and other body parts of the two men and woman. New possibilities are created through such an exchange, and the intertwining of their capacities, abilities and debilities transform concepts of mobility, immobility, pathology, beauty and especially disability. These bodies point towards the need for a new language to assess notions of “support” and insufficiency.

The works of Joseph Grigely, Christine Sun Kim, Park McArthur, Alison O’Daniel, Carmen Papalia, Laura Swanson, Chun-Shan (Sandie) Yi, Corban Walker, and Artur Zmijewski destabilize reductive representations of the disabled body. They create new thinking about bodily experiences and disrupt negative associations of impairment. Their works move away from binaries such as “ability” and “disability” to think radically about what the body can do given more complex theories of embodiment. Disability studies scholar Carrie Sandahl has asserted that “disabilities are states of being that are in themselves generative, and, once de-stigmatized, allow us to envision an enormous range of human variety – in terms of bodily, spatial, and social configurations.”26 Collectively, the artists in What Can a Body Do? offer new possibilities of what constitutes a representable body through their powerful multi-sensorial art practices, and with this, they also expand our thinking about disability itself.

Amanda Cachia is a curator from Sydney, Australia. She recently completed her second Masters in Visual & Critical Studies at the California College of the Arts (CCA) in San Francisco. Cachia received her first Masters in Creative Curating from Goldsmiths College, University of London in 2001 and will embark on a dual PhD in Art History, Theory & Criticism and Communication at the University of California, San Diego in Fall 2012. Her dissertation will focus on the intersection of disability and contemporary art. Cachia has curated approximately thirty exhibitions over the last ten years in the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, and Canada. What Can a Body Do? on wordgathering.com

Bibliography

Books currently held by Tri-College Libraries are linked below.

- Deleuze, Gilles. “What Can a Body Do?” Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza. New York: Zone Books, 1990.

- Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. “Becoming-Intense, Becoming-Animal.” A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

- Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. “Disability, Identity, and Representation: An Introduction.” Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

- Grigely, Joseph. “Nudist Plays: A Dialogue with Joseph Grigely by Ian Berry.” Joseph Grigely: St. Cecilia. Curated by Ian Berry and Irene Hofmann. Baltimore: The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, Contemporary Museum, 2007.

- Kim, Christine Sun. Artist Statement, 2011.

- Massumi, Brian. “Navigating Movements: An Interview with Brian Massumi.” Interview by Mary Zournazi. 21 c. 2002.

- Maxwell, Eamonn. “The Line Begins To Blur.” Corban Walker: Ireland at Venice 2011. Ireland: Culture Ireland, 2011.

- McArthur, Park. “It’s Sorta Like a Big Hug: Notes on Collectivity, Conviviality, and Care.” Cripples, Idiots, Lepers, and Freaks: Extraordinary Bodies/Extraordinary Minds, The Graduate Center of the City University of New York, March 23, 2012.

- Noys, Benjamin. “Introduction.” Georges Bataille: A Critical Introduction. London: Pluto Press, 2000.

- O’Daniel, Alison. Artist Statement, 2011.

- O’Daniel, Alison. Night Sky Artist Statement, 2011.

- Ott, Katherine. “The Sum of Its Parts: An Introduction to Modern Histories of Prosthetics.” Artificial Parts, Practical Lives: Modern Histories of Prosthetics. New York and London: New York University Press, 2002.

- Papalia, Carmen. Artist Statement, 2012.

- Puar, Jasbir. “Prognosis Time: Towards a Geopolitics of Affect, Debility, and Capacity.” Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, 27 June 2012.

- Saldanha, Arun. Psychedelic White: Goa Trance and the Viscosity of Race. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

- Sandahl, Carrie. “Considering Disability: Disability Phenomenology’s Role in Revolutionizing Theatrical Space.” Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism. Spring, 2002.

- Scully, Jackie Leach. “Thinking Through the Variant Body.” Disability Bioethics: Moral bodies, Moral difference. London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008.

- Siebers, Tobin. “Body Theory.” Disability Theory. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008.

- Siebers, Tobin. “Disability and the Theory of Complex Embodiment – For Identity Politics in a New Register.” The Disability Studies Reader. Ed. Lennard J. Davis. London and New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Swanson, Laura. Artist Statement, 2012.

Footnotes

- Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, “Disability, Identity, and Representation: An Introduction,” in Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 7.↑

- Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, “Becoming-Intense, Becoming-Animal,” in A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translated by Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 257.↑

- “What Can a Body Do?” was also the title of one of the chapters in this study.↑

- Gilles Deleuze, “What Can a Body Do?,” in Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza (New York: Zone Books, 1990), 226.↑

- Jackie Leach Scully, “Thinking Through the Variant Body,” in Disability Bioethics: Moral bodies, Moral difference (London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008), 84.↑

- For Foucault’s discussion of subjugated knowledges, see The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (New York: Vintage, 1994).↑

- Jackie Leach Scully argues that embodied cognition bases complex mental processes on the physical interactions that people have with their environment; this is contrasted with the classic or first generation view of cognition as essentially computational or rule-based. See “Thinking Through the Variant Body” in Disability Bioethics: Moral Bodies, Moral Difference (London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008), 84.↑

- Tobin Siebers, “Disability and the Theory of Complex Embodiment – For Identity Politics in a New Register,” in The Disability Studies Reader Third 3rd Edition, ed. Lennard J. Davis (London and New York: Routledge, 2010), 317.↑

- Tobin Siebers, “Body Theory,” in Disability Theory (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2008), 54.↑

- In the “Introduction” of Georges Bataille: A Critical Introduction, Benjamin Noys talks about Bataille’s ‘principle of insufficiency’ which dominates all existence. He says “It means that no being is ever complete, ever sufficient, and that because of this insufficiency every being is in an open relation to others…The most powerful example of the principle of insufficiency is language, because language imposes itself on us and puts us in relation to others…It is language which discloses the impossibility of an autonomous being, and it is language which places us in an impossible relation that we can never master.” (London: Pluto Press, 2000), 14-15. The principle of insufficiency has a striking resemblance to Deleuze and Guattari’s question about what a body can do.↑

- Brian Massumi, “Navigating Movements: An Interview with Brian Massumi,” interview by Mary Zournazi in 21 c. 2002.↑

- Jasbir Puar, “Prognosis Time: Towards a Geopolitics of Affect, Debility, and Capacity” Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 27 (June 2012): 161-162↑

- Arun Saldanha’s reinterpretation of Levinas in Psychedelic White: Goa Trance and the Viscosity of Race (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007) 118.↑

- Joseph Grigely in “Nudist Plays: A Dialogue with Joseph Grigely by Ian Berry,” Joseph Grigely: St. Cecilia, curated by Ian Berry and Irene Hofmann (Baltimore: The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, Contemporary Museum, 2007), 6.↑

- Signing is enormously spatial compared to linear English and so many aspects are happening simultaneously such as grammar, placement, tone, etc.↑

- The majority of people who form the care collective are white artists, academics or organizers, many of whom are queer and politicized. They are in their 20s and 30s.↑

- Park McArthur, “It’s Sorta Like a Big Hug: Notes on Collectivity, Conviviality, and Care,” paper for Cripples, Idiots, Lepers, and Freaks: Extraordinary Bodies/Extraordinary Minds, The Graduate Center of the City University of New York, March 23, 2012.↑

- Alison O’Daniel, Night Sky artist statement, 2012.↑

- Ibid.↑

- Ibid.↑

- In this paragraph, Papalia is using the word “disables” in a new context. While previously I use the noun as a marker of identity that captures physical difference, here, Papalia notes that it is the barriers, attitudes and exclusions – made concrete in architecture and practical engagement – that disable society at large, not just those with physical disabilities. This is the definition of disability based on the social model, where it is society that disables the individual, not the individual who is inherently “disabled” or “deviant.”↑

- Carmen Papalia, artist statement, 2012.↑

- Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (1487) is a drawing of a man that mapped out “ideal” notions of human perfection, proportion, and beauty as defined in classical sculpture. Le Cobusier’s Modulor (1948) was developed based on the tradition of Vitruvian Man. Regretfully, the representation of a bodily ideal in Vitruvian Man and Modulor is still seen as the ideal form today, contributing to ableist attitudes and discrimination against the disabled minority. Thus, Walker is working against these ideal proportions and substituting them with the measurements of his body.↑

- Eamonn Maxwell, “The Line Begins To Blur,” in Corban Walker: Ireland at Venice 2011 (Ireland: Culture Ireland, 2011), 19.↑

- Indeed, as historian and scholar Katherine Ott notes, “analysis and interpretation of prostheses have… come from psychoanalytic theory… The prosthesis has become a literal symbol of more complex issues.” Katherine Ott, “The Sum of Its Parts: An Introduction to Modern Histories of Prosthetics,” in Artificial Parts, Practical Lives: Modern Histories of Prosthetics (New York and London: New York University Press, 2002), 3.↑

- Carrie Sandahl, “Considering Disability: Disability Phenomenology’s Role in Revolutionizing Theatrical Space,” in Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism (Spring 2002), 19.↑