i’m thinking aBOuT bodies.

Bodies with which the world is not prepared to contend. Bodies that systems of colonialism, of white hegemony, have determined to be outliers.

I’m thinking of pristine white outlines of bodies on bathrooms, men and women, women who inevitably wear A-line dresses (that is what it is to be a woman according to bathroom placards: to be white, to stand, to wear stiff dresses). Accessible bathrooms denoted by wheelchairs, as if to be a person whose body works atypically means you are instantly thrust into a chair.

The gap in my knowledge scares me at times. I find myself overwhelmed by the stories I have missed, narratives of modern martyrs and fellow humans whose lives and legacies should be cherished. It took me twenty-five years and two years of curatorial school to learn this story. Perhaps you already know it, or perhaps it will be as new and shocking as it was to me when I heard it a few years ago.

In 1985, Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta plummeted 33 stories from her Greenwich Village apartment. Neighbors had heard her arguing with her husband, artist Carl Andre. Though he was acquitted of her death on grounds of reasonable doubt, many believe his was the hand that pushed her through the window. The 911 call he made haunts me: “My wife is an artist, and I’m an artist, and we had a quarrel about the fact that I was more, eh, exposed to the public than she was. And she went to the bedroom, and I went after her, and she went out the window.” Already it is about prestige, not panic at her loss. “She went out the window,” as if she “went out” to the store or “went out” the door. Casual language. Language that ignores responsibility, agency, the cold reality of death. Defenestration and liberation, a cruel combination.

In the sacred space of my imagination, Ana Mendieta flies. She never lands, but soars, free from jealousy, free from violence, free from fear. I know in reality she must have been terrified. I hope to honor her in this small way and to find in halting her story, in denying Carl her collision, a way to exist in the in-between.

An Alarming Specificity puts that in-between in a room, to devote a space to bodies and beings too often rendered peripheral and in turn subjected to violence. It is the periphery itself made material, made performative. It is realized in the very strategies employed in its making, in its design. In giving us the opportunity to inhabit a space born of otherness, it seeks to uphold and cherish those too often ignored, to celebrate and share tactics that have enabled marginalized bodies and beings to survive and thrive.

a space where our bodies DOn’t have expectaTions thrusT upon them

Each time we tell the story, Ana falls again. I want so badly to keep her suspended by some secret magic. I fumble with the words in my mouth and fail. (It’s LeviOsa not LeviosA, an eternal, inevitable failure.) I can only keep her suspended in story. If we do not read to the end, then within the ink, within the twists of our speech, we can hold her up, still alive, but free from the clutches of those who would do her harm.

In my days at Haverford I was an English major, and no matter how far I stray into the realm of contemporary art, I find myself anchored to texts. Here, echoing James Joyce’s resounding but often unprinted final “.” in Ulysses, I found comfort in the punctuation at the conclusion of Kate Chopin’s 1899 novel The Awakening. In the book’s final pages, Chopin’s protagonist Edna Pontellier, having discovered a new sense of creativity and sexuality, walks out into the water, in what some consider concession and what others see as courage. “She drowns,” said my 12th grade English teacher, in a matter-of-fact declaration of certainty. My mother’s handwriting retorts at the bottom of the last page, in an echoing, unanswered question: “Does she die?” In that question mark I find that longed-for suspension. The question creates a space between between life and death, between power and deficit. The question serves as the bridge, joining the two, forcing an instantaneous relationship between them.

My mother insists that she doesn’t drown. We never see Edna’s body. The novel concludes with a series of sensations, sounds, the barking of dogs, the hum of bees, the odor of pinks in the air. Edna becomes sensation itself, and the sensations only halt as the flow of ink ceases with a telltale “.” That final period finds shelter in my mother’s question mark. On that dot, Edna floats. We, within that tiny speck of ink, can hold her up, perpetually alive in the sea, near death but ever undying. My mother kept her alive for me. She taught me the secret, this magic trick, made of equal parts denial and hope. To stop at the border, to exist both alive and dead, is never to be fully dead. We claim the power of Schrodinger’s Cat, clawing at box walls, perpetually present even in our absences. There is a difference between quitting and stopping. Here, we quit. We let her float. We do not extrapolate, we defy inference, and Edna lives. Edna is but fiction though, and Ana is real, flesh and blood and bone. And she is gone, out the window and to the earth, to dust she has returned.

Linda Stupart After the Ice, the Deluge, performance documentation, Svalbard archipelago, Summer 2019. Photograph Ryan Sloan.

Linda Stupart After the Ice, the Deluge, performance documentation, Svalbard archipelago, Summer 2019. Photograph Ryan Sloan.

Between the window and the pavement is a space where our bodies don’t have expectations thrust upon them. In the ether, unbounded by materiality of floors, of windows, of chairs, nothing is the wrong height, no skin the wrong color. Nothing is the wrong sex, the wrong preference. To operate within the margins defies these insistent acts of marginalization, both large and small. Floating, we are alone. -9.8 meters per second per second of acceleration. If we could just stop accelerating. Stop the velocity. Just pause in the air. Bodies can’t not fit, can’t be wrong, suspended in the air.

Freedom should not be so hard-won, nor so agonizingly brief. It should not be bookended by violent egress and an agonizing passage into that good night. It should not be instigated, forced by another. There should be more ways to be in the in-between.

An Alarming Specificity is my attempt to explore the in-between. I have been fortunate to develop this project within the realm of Assistant Professor of Religion Molly Farneth’s faculty seminar “Borders and Boundaries.” She and Hurford Center for the Arts and Humanities Director Ken Koltun-Fromm asked me at the start of this project to think about ways boundaries function as part of exhibitions, about the varying ways boundaries manifest in the human experience. The line between the typical and atypical body loomed largest for me as I began my research. But another theme emerged within this sphere: sovereignty. So much of these constructions of otherness derives from the paradoxical nature of sovereignty: the sovereign state’s attempts to protect the sovereignty of the individual body inherently limit, and even damage, the very sovereignty of that body. It’s the curse of Hobbes.

Part of this issue lies in the differing views of whose bodies get to have sovereignty. For too long it’s been white, cis, straight men who determined that which constituted a body worthy of sovereignty, with themselves as the predominant model. The protection of their sovereignty defined and delimited that of others. Over time the definition of sovereignty has slowly expanded as our shared sense of what is typical of humanity has shifted, hard-fought and hard-won by innumerable people. In marches, in riots, in acts of protest large and small, our forebears and our peers have expanded the definition of a body to include more and more of us.

Yet in so many ways, the material world continues to reinforce certain bodies as constituting outsiders. Digital cameras struggle to capture black skin, reechoing Kodak’s Shirley cards of the mid-twentieth century, which determined whiteness as the quintessential quality of skin tone. Facial recognition operates without acknowledgment of non-binary or trans identities. According to the Human Rights Campaign, twenty-five trans and gender non-conforming people, most of them people of color, were murdered in 2019. LGBTQIA+ families struggle for recognition to adopt. Heart attack symptoms in the medical field are aligned with men’s symptoms, resulting in the death of women whose symptoms manifest differently. We can’t even begin to name the people of color arbitrarily killed. Access to healthcare is in large part determined by ability to work, with one’s right to heal and survive being defined by one’s contributions to capitalism. Exhibitions expect standing bodies, and the image of disability is tied to wheelchairs. Car seats are designed for men, leaving women vulnerable on the road. Haverford College, and in turn the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, exists on the land of the Lenape tribe, the first tribe to sign a treaty with the United States, the first to have land set aside for them in New Jersey, relocated to an elsewhere determined by white men. We exist in an era of Me Too and Black Lives Matter, having to stake a claim for recognition of the vulnerability of our embodiments in light of acts of aggression and aggression through bias and ignorance. In turn, we must contend with our own complicity in the marginalization of others.

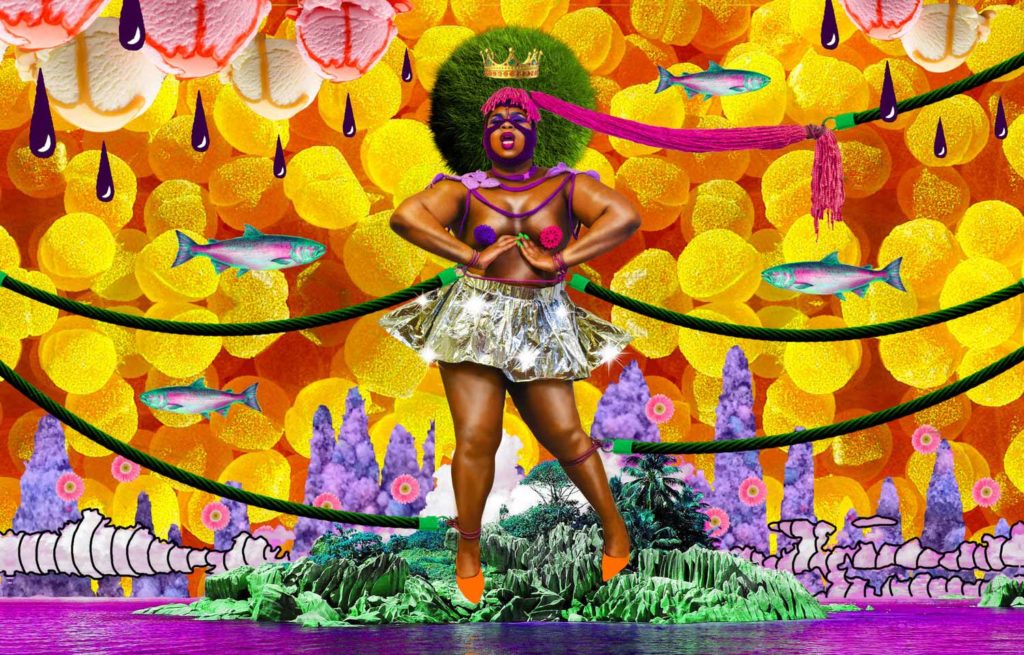

Eva Wŏ, Bad Bitch n Chill [with Kh, Kirby, and Keishi], 2018.

Eva Wŏ, Supreme Queen in Charge [with Icon Ebony Fierce, and costuming by Wit López], 2018. Digital collage for light box.

We bear witness to material worlds not created to hold, to protect, to recognize, to heal too many; a world designed for white, cis, straight, non-disabled, neurotypical men, with the rest, the majority, cast into a supporting role as minority. This world, unprepared to contend with the alarming specificity of our bodies, paints us as marginal inconveniences. “The average woman is an outlier,” quips Caroline Criado Perez in an interview with the BBC about her book Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men.

I must admit that I’m not good at being angry, and that for too long the idea of anger scared me. It’s a skill to be angry, one I’ve had to learn and hone over the years, and one that I, with my privileges of whiteness, of solid US middle classness, had the luxury of developing over time. I often find myself in exhibitions that exist at arm’s length from the curator, in a spirit of preserving some kind of cool objectivity. I have even worked this way myself, but in An Alarming Specificity, I found myself closer to the subject than ever before. I have found my anger a helpful guide, spurring me onward, a way of engaging with my work that has been more productive than ever before, even as it leaves me feeling more vulnerable than ever. And I have increasingly found that anger, rather than being antithetical to happiness, can carve out spaces for joy, for community, for profound togetherness.

Shows I curate exist first and foremost as a sensation. This one has been held twisting and turning in the top of my belly, just beneath where my breasts hang. This feeling gushes and oozes, eternally and spectacularly disgusting, amorphous. I got tired of tidy lines and presumptions of clear logic, the delicious predictability and illusion of transparency that is academia at its most cliché. This show was born of metaphor, wrapped in Linda Stupart’s Virus, suckled by Johanna Hedva’s “Sick Woman Theory.” I spoon fed it Gloria Anzaldúa, Franz Fanon, Augusto Boal, Jane Bennett, Donna Haraway. And then it began to gobble fiction, faerie tales, and sketches in margins and listicles thieved from reddit, novels I glimpsed in the hands of middle school girls, small magicks. And it grew. It blossomed. Inside this squishy amalgam a hard knot of anger coils in on itself, giving root to this tumult.

We gather here not to fix the ills and isolations of the past and present. There is no remedying the harms done to us and to each other, only acts of remediation which inevitably fall short. Please understand, I do not intend to equate the types of harm done. Fatphobia, homophobia, racism, colorism, sexism, transphobia, colonialism, and ableism share roots in hatred derived from constructions of otherness, but the lived experience of the bodies subjected to this litany of phobias and -isms, some singularly, some in tandem, remain decisively different. Attempts at intersectionality too often leave people behind, ignoring those it claims to embrace. Instead, An Alarming Specificity constitutes an attempt to share tactics for survival, to learn from each other in hopes of enabling each of us in this majority cast as minority to thrive.

In Chitra Ganesh’s Double Vision, we find power in material culture associated with women. Fingernails become fearsome, tousled curls containing a multitude of thoughts and sensations. This is a woman, and particularly a woman of color, as creative force, able to capture herself in a camera, able to share herself and her strength with others through the magic of image making.

Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Seduction operates on the other end of the spectrum, toying with and claiming what Laura Mulvey christened “to-be-looked-at-ness,” boldly incorporating technology into her being. Hershman Leeson pioneered the avatar, acting as an entirely separate being, and here we witness the thinking that led to the birth of her avatar character. What power lies in controlling what others see, in their responses? Her siren song echoes in the bold lines of the image, drawing us in even as it leaves us vulnerable to her soon to emerge gaze.

Eva Wŏ’s lightboxes and gifs celebrate queer people of color in lush, surreal landscapes. Wŏ positions her subjects at the center, larger than life in their own universes which protect and celebrate them in a cacophony of brilliant colors. Even as the work honors the bodies of her models, Wŏ recognizes their vulnerability, providing a salt circle and LED candles as a means of protection.

Shannon Finnegan, documentation of Anti-Stairs Club Lounge 2017–2018 at Wassaic Project.

Shannon Finnegan, documentation of Anti-Stairs Club Lounge 2017–2018 at Wassaic Project.

Shannon Finnegan, documentation of Anti-Stairs Club Lounge 2017–2018 at Wassaic Project.

Yvette Granata’s installation draws from the history of natural hormone hacking, particularly abortion-inducing plants. Fascinated by the circulation of knowledge, especially among women who pursued abortion in defiance of the law such as enslaved women in the 18th and 19th centuries, Granata’s Bosch-inspired installation examines key plants used to induce abortions, while also cautioning against the danger the natural world can hold.

Shannon Finnegan’s Anti-Stairs Club Lounge in the elevator considers intermediary spaces as places in which time is spent, rather than containers for passing moments. Operating in buildings which feature stairs as a solitary means of entry or as the predominant architectural point (The Whitehead Campus Center which houses the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery being the latter), Finnegan asserts the value of alternative experiences even as she cautions against allowing assumptions of what bodies can do to govern architectural design. Coupled with her seating intervention in the gallery, Finnegan activates underacknowledged spaces as critical parts for the experience of witnessing artwork.

Within Linda Stupart’s work, we grapple with connections between queerness and climate. Stupart’s performance and subsequent installation explore the vulnerability of bodies and the natural world. Utilizing film they took while researching in the arctic, Stupart’s After the Ice, the Deluge (The Awakening) finds warmth even in the coldest of climes.

I hope you leave this space feeling cherished, feeling your frustrations recognized, acknowledging where you yourself have fallen short and where you can do better work in supporting others. Let the alarming specificity of our bodies cause not panic but joy and possibility. This world not made for us we remake together, in our own images. Here anger and hope can coexist, simultaneously frustrated at forced marginalism even as we dance in the liminal space they have made for us. Here we are together, and I hope for you it is as encouraging and edifying as this process of making has been for me.